“We must prioritise managing risks, not crises,” urged Håkan Tropp, COO of the Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI) and head of the OECD Water Governance Programme, from the stage of the Climate Change Summit 2024.

His message perfectly encapsulates the situation that Asia is finding itself in regarding water scarcity. The region is already facing significant water supply disruption and is also among the most vulnerable to climate change. Changing climate patterns, including unpredictable rainfall, prolonged droughts, floods and storms and global warming-induced glacier melting, significantly disrupt water availability and threaten the region’s water security. Without urgent intervention at the national and sub-national levels, the number of people without access to a basic water supply in the region will only continue to grow.

Asia’s Increasing Water Scarcity Problem

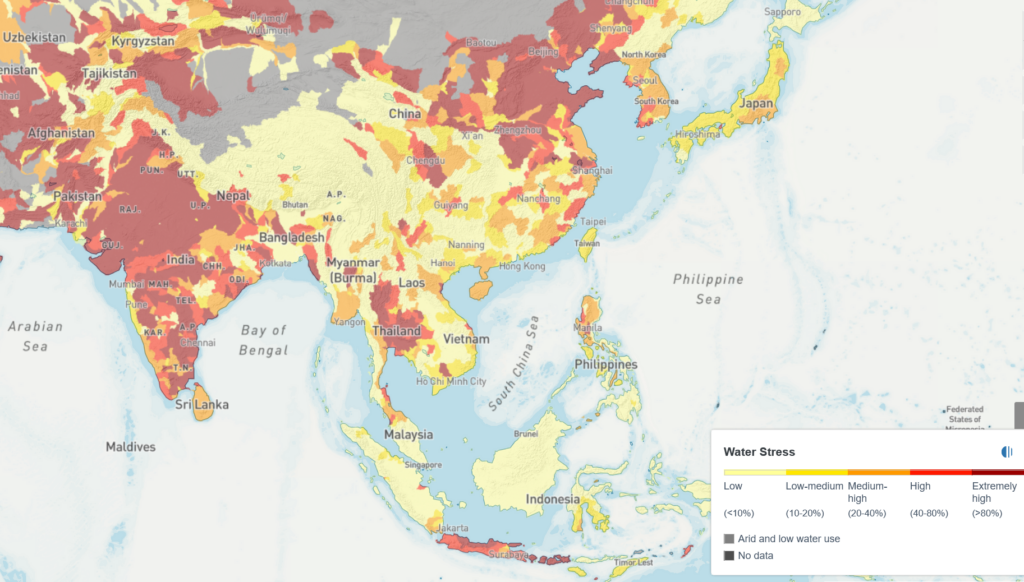

Over 75% of Asia faces water insecurity, with countries home to over 90% of the region’s population already confronting an imminent water crisis.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations finds that some of the most water-scarce areas globally are in the APAC region. Between 1975 and 2010, the population under high or severe water scarcity grew from 1.1 billion to over 2.6 billion. According to the Asian Development Bank, around 500 million people in the region lack access to a basic water supply today.

In Southeast Asia, 110 million people lack safe drinking water, with 74% of the population grappling with high water stress levels. Disturbingly, 347 million are facing severe water shortages due to climate change – the highest rate worldwide. Furthermore, UNICEF estimates that between 68% and 84% of the water sources in the region are contaminated.

“The main water-related problems we face currently include too much, too little, or too polluted water. Different countries face different degrees and combinations of these problems,” said Tropp.

China and India

China faces a severe water crisis due to the drying up of its biggest rivers, rising water demand and melting glaciers. Up to 90% of the country’s groundwater resources are unfit for consumption, and 50% of the river water is unsuitable for drinking.

India is also affected by water shortages. According to the World Bank, its water resources are sufficient for only 4% of the population despite the country having 18% of the global population.

However, although the two countries face big challenges, unlike other Asian economies, they also have sufficient resources to address them.

Vietnam

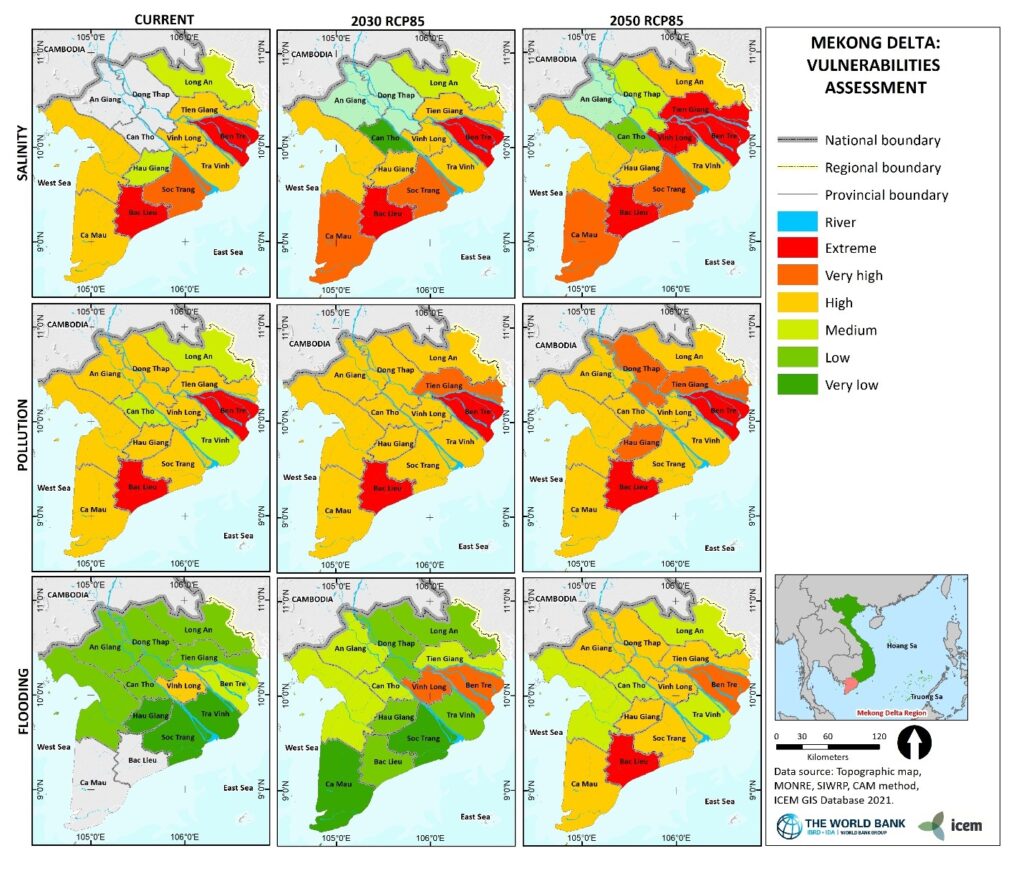

Vietnam experiences all types of water scarcity, including too little water, water supply intermittency, poor water quality and overutilisation. A big reason for the water scarcity problems is that around 63% of its surface water comes from transboundary rivers, making it highly dependent on the actions of upstream countries. Access to safe drinking water is also threatened by the increased rate at which clean groundwater is pumped for industrial, agricultural and urban use.

However, natural factors and the worsening of the climate crisis also play a big part. The 2024 saltwater intrusion in the Mekong River, which 65 million people rely on, arrived way earlier and was more significant than usual. It prompted recurring water cuts, complicated access to clean water for household use and disrupted rice and crop production.

Indonesia and Thailand

Indonesia suffers from water that is too variable, overutilised and of poor quality. Studies estimate that only 10% of rainfall infiltrates the groundwater. Around 70% of the rivers are heavily polluted by domestic waste. Increased deforestation and agricultural runoff are also exacerbating the water stress.

Thailand experiences all types of water scarcity, including too little water supply, too variable water, overutilisation and poor water quality. The water quality issue is a particularly notable problem for the entire country due to industrial and agricultural pollution, high population density and low wastewater treatment rates.

Bangladesh

According to the FAO, Bangladesh experiences two types of water scarcity – highly variable water and poor water quality. Furthermore, analysis has shown natural arsenic contamination in the groundwater in 60 out of the 64 districts in Bangladesh.

Today, while 97% of the population has access to water, just 40% enjoy proper sanitation. In coastal areas, people walk miles daily to access safe, drinkable water.

Furthermore, groundwater is depleting rapidly in the greater Dhaka area, posing a risk of permanent water loss. According to studies, by 2030, groundwater levels can drop by up to 5.1 m. This is around 70% faster than the current rate.

The magnitude of the problems is so significant that Bangladesh is now approaching a situation of chronic water scarcity. Estimates reveal that it could cost the country’s economy up to 6% of its GDP in 2050.

Climate Change Is Exacerbating Asia’s Water Scarcity Problems

There are various triggers for Asia’s water stress, including infrastructure build-up and uncoordinated development, a growing population and increasing water demand, increased consumption for industrial purposes, land use changes and pollution.

“By 2050, over 4 billion people will live in water-stressed areas. Over 60% of the global population will live in cities, with Asia having some of the highest urbanisation rates. This would change the lifestyle and water demand dynamics,” said Tropp.

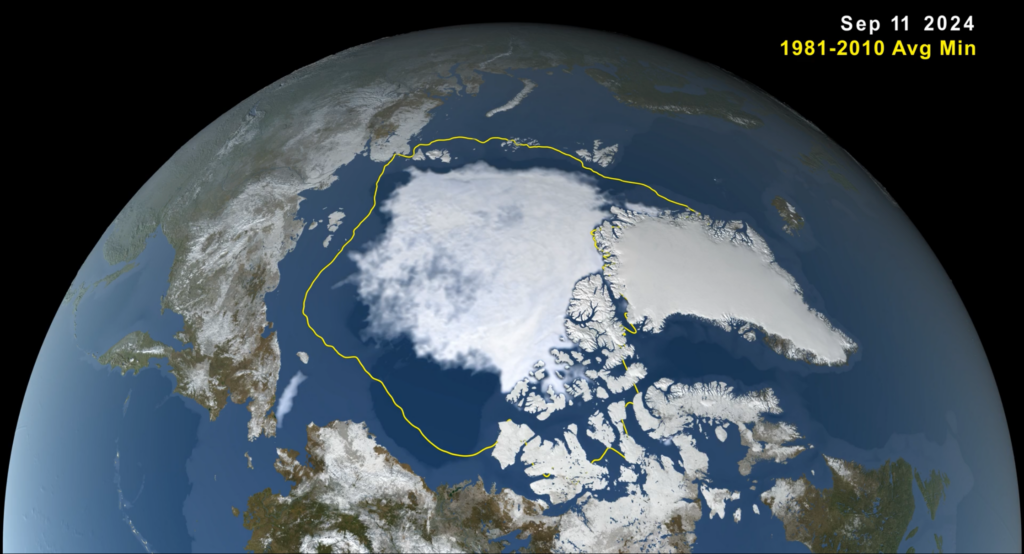

However, scientists are confident that climate change and its diverse impacts are among the biggest contributors to Asia’s increasing water stress. Water and climate change are deeply linked, as rising temperatures disrupt the entire water cycle, including precipitation patterns and droughts, affecting ice sheets and sea levels and causing more severe floods and storms.

“Climate change and factors like changing precipitation patterns will significantly impact water supply. As a result, we can expect too much or too little water supply at the wrong time,” explains Tropp.

According to the IPCC, sea-level rise will extend groundwater salinisation, decreasing freshwater availability in coastal areas. Furthermore, the scientists warn that the relative sea level around Asia is increasing faster than the global average, and their high-confidence projections reveal that the regional mean sea level will continue to rise. As a result, Southeast Asia bears some of the highest coastal flood risk globally.

Meanwhile, erratic monsoons, storms, floods and rising sea levels can all lead to saltwater intrusion. This process includes saltwater advancing through surface or groundwater sources to diminish the availability or quality of drinking water supplies. Countries across the Mekong River, the biggest river in Southeast Asia, face multiple drivers and anthropogenic forces that will increase the salinity of affected areas by up to 27% in the next three decades. Rising sea levels will add another 6-19% increase. According to researchers, severe saltwater intrusion negatively impacts health and can contaminate soil, reduce crop harvest and change species abundance and diversity.

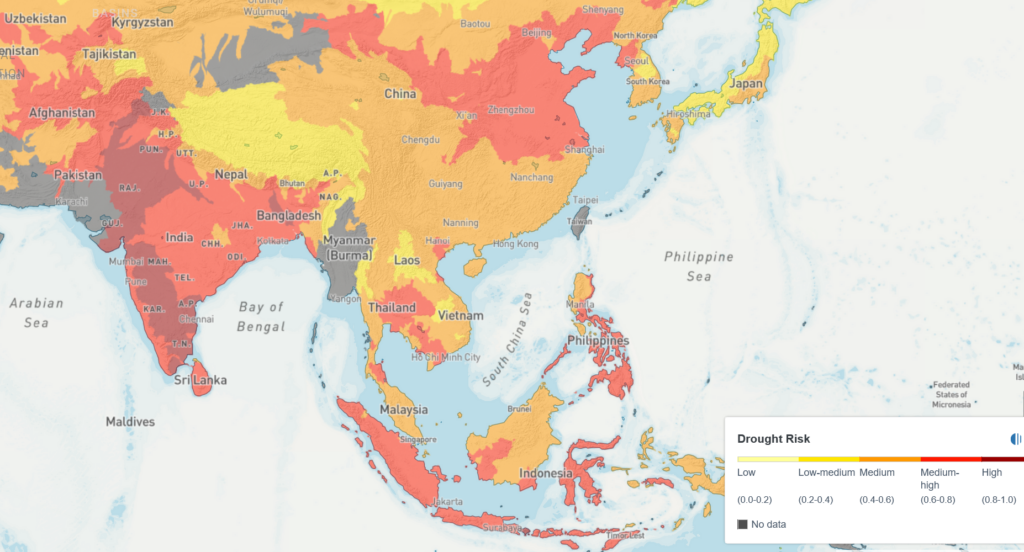

However, having too little water is also a risk, especially in South and Southeast Asian countries, which will experience medium-to-high or high drought risk in the upcoming years. Furthermore, scientists warn that the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, which provide water to almost a billion people in South Asia, including some of the poorest and most marginalised population groups, are all at risk of drying up.

According to scientists, the Indus Basin, which supplies water to northern India and Pakistan, is at risk of experiencing a 79% decline in water supply capacity by 2050. The authors warn that in a business-as-usual emission scenario, we can expect a near 100% loss of water availability to downstream regions of the Tibetan Plateau. Even in a best-case scenario, further losses are likely unavoidable.

Another risk factor is the accelerated warming of the Himalayan glaciers, a vital ecosystem for Asia’s major rivers and on which almost 2 billion people rely for agricultural use and drinking water. Scientists warn that over past centuries, they have been warming over 10 times faster than average. The glaciers risk losing up to 30% of their mass by 2030 and 75% by 2100, potentially causing dangerous flooding and water shortages.

Some experts believe that the melting glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau could spark geopolitical conflicts –mainly between India and China – with consequences for the entire continent. As a result, they suggest prioritising more ambitious climate policies and focusing on adaptation to decreasing water resources.

Solutions to Asia’s Water Scarcity Exist

“In the future, there is a risk of not having enough water for everyone. That is why it needs to be shared, and we should work collectively,” explains Tropp.

According to him, increased collaboration and improved water governance practices are crucial.

“Water crisis is often a governance crisis, so it is about how we change and govern water as a society,” the expert explains.

His team at SIWI and partners launched the Global Water Cooperation index, an initiative to track transboundary water cooperation across 149 countries. Using a set of different factors, it analyses various aspects, from sub-national and national to transboundary water cooperation preparedness.

According to the index, most Asian countries are progressing, although the region, as a whole, is near the global average. Considering the magnitude of the challenges facing Asian countries, more efforts are needed to avoid climate-change-related water stress risks.

The latest Transboundary Water Cooperation report by the UN finds that transboundary water cooperation in Asia is low. Only two out of 41 countries sharing transboundary waters have 90% or more of their transboundary basin area covered by operational arrangements. By 2030, the figure should increase to 25.

Current good practices in transboundary water cooperation include the Mekong River Basin, with the Lower Mekong countries (Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam) collaborating under the 1995 Mekong Agreement. Cooperation with upstream countries, such as China and Myanmar, continues to evolve through the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Mechanism. However, according to the UN, comprehensive basin-wide operational arrangements are needed for crucial regions such as the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna river basins (Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, and Nepal), Salween River Basin (China, Myanmar and Thailand), Irrawaddy River Basin (China, India and Myanmar) and Red River Basin (China and Vietnam).

“Water management is really fragmented. That is why it is crucial to ensure cooperation between different stakeholders and sectors such as governments, the private sector, civil society, farming communities and more,” explains Tropp.

Another crucial aspect is improving water integrity by addressing corruption and dishonest practices, which threaten to slow down or even derail efforts to tackle water stress. According to statistics, 20 to 40% of water sector finances are lost to dishonest practices.

“While the water quantity is fixed, the demand is increasing, with a 50% projected growth over the next thirty years. We need to make better decisions today to manage the water demands of tomorrow,” warns Tropp.

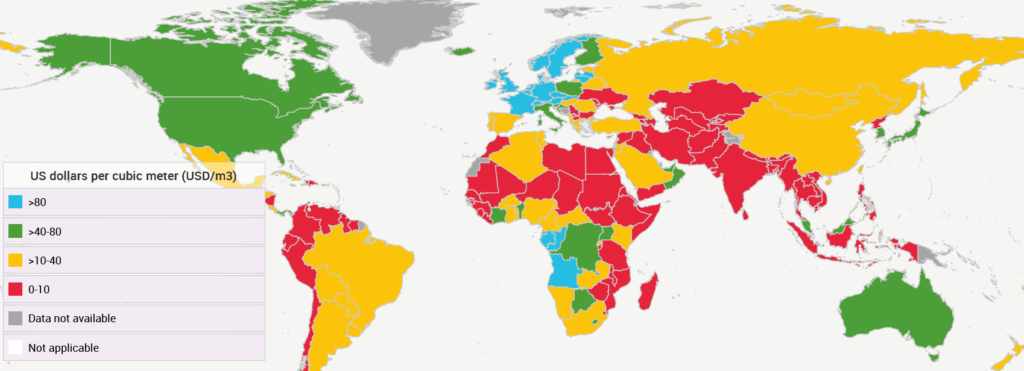

Improving water use efficiency is crucial for this. According to the UN, Asia currently has some of the lowest value added from water use. Only Malaysia (USD 58 per cubic metre) and China (USD 31 per cubic metre) score above the global average of USD 21 per cubic metre. For reference, countries like Pakistan, India and Indonesia generate an economic output as low as USD 2-4 per cubic metre of water used.

Measures such as repairing leaking water distribution systems, using less thirsty crops and investing in new technology, for example, are crucial for improving water efficiency. As a result, countries can expect to reduce the water stress risk they are exposed to, ensure more sustainable food and industrial production systems and save energy.

According to Tropp, prioritising nature-based solutions to the increased water stress is another important area to focus on.

“We should learn to use nature in a smart way, starting by preserving it so that we can capitalise on its benefits. If we take wetlands, for example, first, they purify water as it circulates in the wetland ecosystem. Next, if there are heavy rains and floods, wetlands can function as buffer zones and mitigate floods,” notes Tropp.

According to the expert, the way we use water is crucial for reducing the risk of conflicts and avoiding alleviating poverty while at the same time fostering socioeconomic development and supporting healthy ecosystems and services.

“If we are going to solve our challenges, societies, governments, the private sector and research communities must work together. We should all be in the same room and not allowed to leave until we have resolved the situation.”

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.