According to climate scientists, who analysed 146 past and current generations of climate models in joint research, Asia will become significantly exposed to extreme rainfalls and flood risk by the decade’s end. While between 3-5 billion people globally will be affected by 2100, no continent will face such substantial rainfall changes as Asia.

Hwayoung Yoo, a farmer from Nonsan in South Korea, hopes the rains would stop. “I don’t have a religion, but I still prayed for it to stop raining,” said Yoo when talking about the floods of 2023. “The water level reached to my waist. I had never been so desperate in my entire 53 years of life,” added Yoo, who gave up the bustling city life eight years ago to start farming in South Korea’s countryside.

“Everything was flooded, and it took about a month to dry my fields and start planting again,” she said. “But new crops and vegetables were damaged by diseases and insects that I had never seen before.”

When asked about how she envisions the future, Yoo said: “As climate change is worsening, I fear that I will have to deal with more disasters.”

Asia as the Future’s Hotspot For Extreme Rainfall

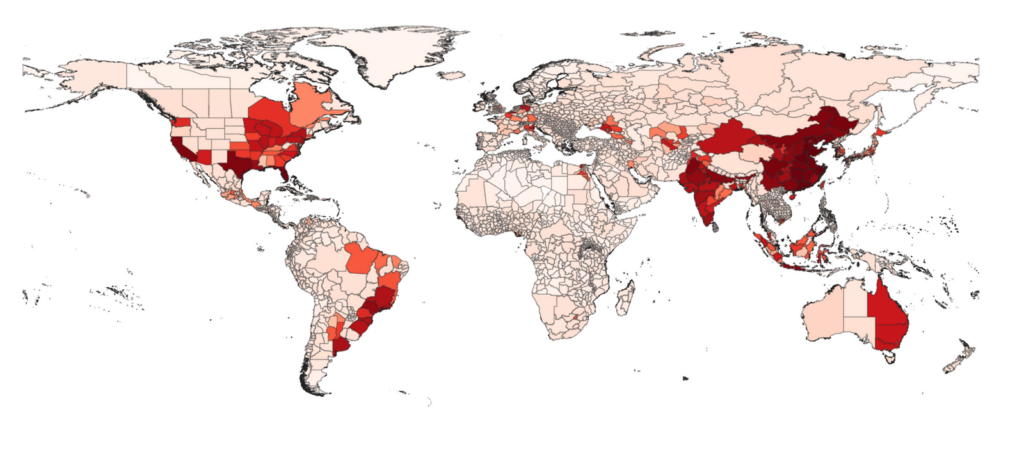

Of the 25 countries that have the highest risk of extreme rainfalls by the end of the century, 10 are in Asia. Over 70% of the examined models show that highly-populated areas, home to over 2.7 billion people in China and India, will experience increased rainfall. The rest of the affected Asian countries include Bangladesh, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia.

More disturbingly, the study’s authors note that their work overcomes the uncertainty of previous research on the matter and confidently identifies the future hotspots for wetter weather conditions.

However, many people across Asia don’t need further convincing when it comes to the changing climate. People in the region have been experiencing it first-hand for years.

Another farmer, Jeongyeong Kim, from Sangju in South Korea’s North Gyeongsang Province says that farming has changed due to the climate. “Things are different from the past, and we have to deal with so many uncertainties,” says Kim.

“Growing crops and vegetables is getting difficult due to climate change. It seems like we don’t have four distinct seasons anymore. The spring is getting shorter, while, in the summer, it is becoming too hot, and we have too many heavy rainfalls,” Kim explains.

Studies find that, since the late 1970s, typhoons in the East and Southeast Asia parts have doubled in their destructive power, while the number of Category 4 and 5 storms have doubled or tripled. According to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) Assistant Secretary-General Dr. Wenjian Zhang, people can expect stronger winds, heavier rainfall, higher waves, storm surges and coastal flooding as a result of the increasingly intense tropical cyclones.

In two years, extreme floods due to heavy monsoonal changes have also been tormenting countries all across Asia, taking lives, destroying livelihoods and impacting economies.

A common denominator during these instances over the past two years is the role of flash floods – a situation occurring when particular hotspots experience a substantial amount of rainfall in just a few days or hours.

“Last September, it again rained a lot, and I was worried about another flooding. Luckily, nothing serious happened, but I couldn’t leave my fields until it stopped raining very late at night,” said Hwayoung Yoo. “I had to check all the waterways.”

Rising Sea Levels Increase Flood Risk

After studying the modelled projections of damage to the built environment from extreme weather and climate change impacts for over 2,600 locations worldwide, the Cross Dependency Initiative (XDI) ranked Asia as the region with the highest risk.

In its 2023 Gross Domestic Climate Risk Dataset, the expert group in physical climate risk concluded that 114 of the top 200 provinces with the highest aggregated damage ratio by 2050 will be in Asia. The biggest risk is identified in East and Southeast Asia, with 29 of the top 200 provinces in China, another 20 in Japan and four in South Korea. Southeast Asia, notably Vietnam and Indonesia, holds 36 of the top 200 places in the ranking.

XDI’s findings align with the conclusions of another study by the World Bank. It warns that while flood risk is a global threat, 70% of the most flood-exposed people (1.24 billion) live in South and East Asia.

According to XDI’s models, between 1990 and 2050, East and Southeast Asia will experience the most significant increase in damage globally, with the steepest escalation being post-2030. The two leading reasons are sea level rise and flooding risk.

After conducting a satellite survey, a research team at the University of Rhode Island in the US found that 17 of the 20 fastest-sinking cities between 2015 and 2020 were in Asia.

Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, for example, is the fastest-sinking city globally, with a third of its territory on course to be submerged by 2050. This even prompted Indonesia’s leadership to start building a new capital.

Suwarno, a 55-year-old builder from Manggihan, Demak, in Indonesia, says, “The first time a tidal flood hit was in 2006. The water level immediately reached half a metre into the house.”

According to him, the situation has worsened over time. “The water level keeps rising. Tidal floods became frequent. Our village has been submerged by seawater,” he recalled. “Currently, another village in Mondoliko has been isolated. Everything is submerged – roads, houses, public facilities, and mosques. There is no life there anymore.”

Suwarno said that the impacts have affected his daily life. “My health, mentality, finances – еvery day I felt tired mentally and physically. Not to mention my sons, whose education was disrupted,” he said.

He even tried several expensive construction alterations to his home. However, there was little to no effect when it came to the floods. “Today, my house is submerged by tidal floods and sinking. I didn’t feel at home there anymore. Thinking about my children’s future, I had to rent a house to continue my life.”

Indonesia isn’t the only country at risk of rising sea levels and tidal floods. Sea levels in the Philippines have risen to double the global average from 1951 to 2015. Greenpeace Asia notes that Metro Manila is sinking by 10 cm every year. Some studies even predict that coastal flooding events in Manila will occur 18 times more often than before due to climate change.

Vietnam is found to be the most at risk of coastal flooding in Southeast Asia. Both Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, which are located near highly flood-prone deltas, are especially vulnerable.

By 2030, 96% of Thailand’s capital, Bangkok, could be flooded, while 80% of Mumbai could end up underwater by 2050.

Solutions: Urgent and Significant Emissions Reduction Remains Critical

Climate scientists say that the only way to avoid the worst scenarios in their studies is immediate and deep CO2 emissions reduction.

Aside from having the responsibility of leading by example when it comes to reduction, the world’s top three emitters, China, the US and India, also have the most to gain. XDI’s study reveals that the three countries will face the highest aggregated damage risk in 2050.

In order to avoid this, these nations must take action – and take it quickly.

However, in Asia, until such broad-level climate change mitigation action is taken, governments will need to prioritise the needs of their affected communities and scale up their adaptation efforts.

“My town has been designated as a special disaster zone affected by heavy rains and floods, but I haven’t received any support,” said Yoo regarding the lack of assistance from South Korean authorities.

Suwarno’s case is also similar in Indonesia. “There is always basic food assistance, but there has been no assistance from the government regarding relocation,” he says.

When asked about how the government can help, Suwarno says, “I would like to see tidal flooding addressed in my old neighbourhood. Perhaps, for example, by building a coastal belt so that the coastal areas in Java aren’t severely affected by tidal flooding.”

Hope Lies Within Government Decision-making

People on the front lines are often left alone to deal with the extreme weather impacts. However, there is only so much one can do on an individual level. Minimising the projected climate change impacts requires a collective effort, with governments taking the lead through urgent and more ambitious adaptation and mitigation efforts.

“I know we have to diversify the crops and vegetables we grow to minimise the impacts of natural disasters as an individual farmer, but I believe the ultimate solution should be sought by all our society, including the government taking necessary action,” says Kim.

“Honestly, I don’t know what to do to cope with climate change. The biggest concern is that I’m losing hope that things will get better.”

While farmers make their best efforts to mitigate the climate’s impacts, it is the role of governments to ensure the establishment and success of adaptation and mitigation strategies across the board. Without these, nations will be subject to the full force of the climate and its serious impacts.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.