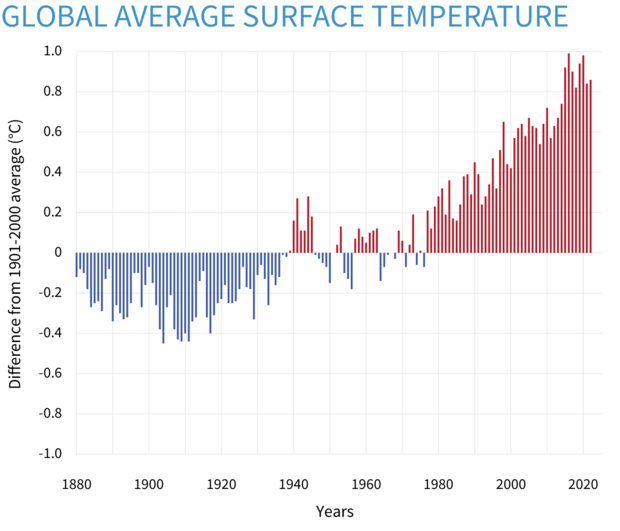

Climate change is transforming the world, and climate change adaptation is critical to protect global communities. The rate of sea level rise has doubled since 1993, global average temperatures are 1.15 degrees Celsius higher than pre-industrial times, and ocean surface temperatures are continually increasing. Scientific trends and climate data point to the climate changes already occurring in warming world, and predict more dramatic climate changes further in the future.

The impact of these changes is affecting millions of people. As of 2021, 2.3 billion people have faced food security issues. And since 2008, 21.5 million people have become climate refugees on average each year. Adapting to climate change, particularly extreme weather, is one of the main ways to reduce risk and make communities more resilient and sustainable in the coming decades.

Climate Change Adaptation vs Climate Change Mitigation: We Need Both

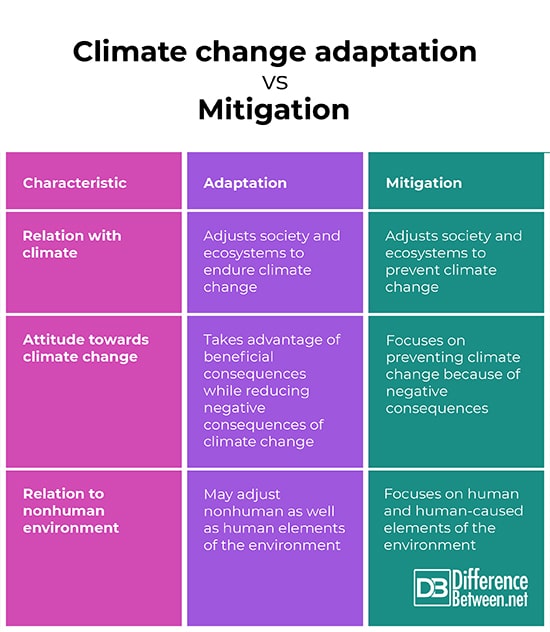

Mitigation focuses on limiting climate change from occurring, by reducing emissions of heat trapping greenhouse gases, whereas adaptation actions aim to help existing communities and ecosystems become resilient to the climate changes and reduce the vulnerability of natural and human systems. Climate change adaptation can take the form of changes in the processes, practices or structures that limit damages or create benefits from the changing climate.

Both mitigation and adaptation have essential roles to play and work hand-in-hand in the world’s response to human-caused climate change. We need both for addressing climate change properly and for sustainable economic development.

Global Climate Adaptation Costs Are Rising

Climate adaptation is an expensive yet necessary process. The United Nations estimates that global adaptation will cost between USD 160 billion and USD 340 billion annually by 2030 and increase to over USD 560 billion annually by 2050. In simple terms, adaptation costs rise as climate impacts become more extreme.

Viewing this trend, it appears economical to invest heavily in adaption within the coming decade while costs remain low, reducing adaptation costs in the long term. Another incentive to funding adaptation is the benefit-cost ratio, which is highly favourable at up to 10:1.

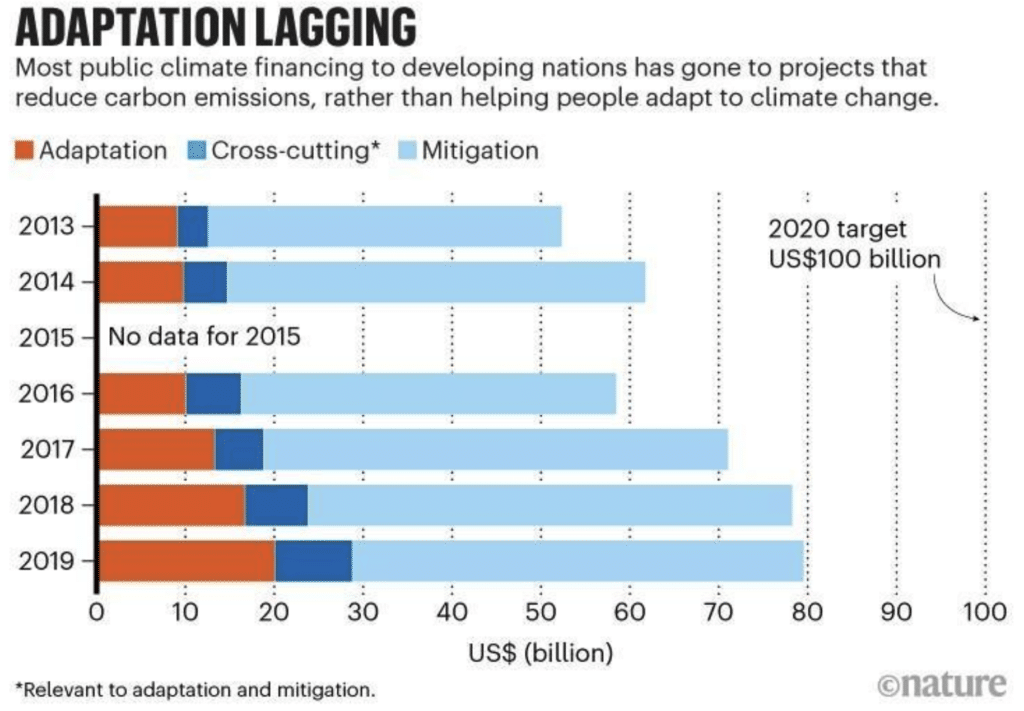

However, climate change adaptation funding remains extremely poor on the world stage and is currently less than one-tenth of the 2030 annual target. This concern is a regular discussion at annual COP meetings, but there is still no roadmap for reaching this funding milestone

More investment and global cooperation are needed to fund climate change adaptation across the world.

“We are in a race against time to adapt to a rapidly changing climate. Adaptation must not be the forgotten component of climate action,” said United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres. “We have both the moral and clear economic case for supporting developing countries to adapt and built resilience to current and future climate impacts. The race to resilience is as important as the race to net-zero.”

One of the main reasons why adaptation costs are so high is because adaptation is far-reaching and encompasses all parts of society. This creates multiple options when considering how to adapt to each threat or community.

Additionally, each individual approach has a role in the larger national or global adaptation strategy, from infrastructure and technology to behavioural and cultural changes and nature-based solutions.

What Are the Four Components of Climate Change Adaptation?

There are four components of climate adaptation: structural, physical, social and institutional. For ease of discussion, the IPCC further groups these components into three categories:

Structural and Physical

This category comprises structural, engineering, technological, ecosystem-based and service options.

- Structural and engineering strategies involve building infrastructure for adaptation. Most people initially think of this as climate change adaptation, like building stormwater drainage systems to reduce flooding.

- Technological strategies entail using technology and information for adaptation, like breeding plant species to be drought resistant.

- Ecosystem-based strategies harness natural ecosystem services, like restoring mangrove forests to reduce coastal erosion.

- Services are activities to facilitate adaptation, like developing public health services to respond to increasing rates of disease.

Social

Social options are commonly referred to as community-based adaptation strategies. They provide educational, informational or behavioural training and services to vulnerable groups. Examples include teaching communities about the benefits of conservation and developing tsunami early warning systems for island nations.

Institutional

Institutional adaptation encompasses large-scale and society-wide economic, regulatory or governmental policy changes. Meanwhile, institutional changes have the power to make sweeping changes across communities. Examples include government policies for developing disaster relief funds and zoning development laws.

There Are Many Strategies for Climate Change Adaptation

Typically, each discrete option for adaptation solutions falls into one of the four categories, yet it will be part of a larger plan encompassing several national adaptation plans and approaches. Combined, these make an adaptation strategy, which is implemented locally, nationally or globally.

Climate change adaptation strategies rely on multiple components to be effective at scale and in various parts of society.

Five Ways To Adapt to Climate Change

Climate change impacts are highly variable, so adaptation strategies are often unique to the risk. Therefore, adaptation requires an assessment of the potential effects and a well-rounded approach to handling them.

Understanding how adaptation can be applied successfully in different situations is a valuable part of global cooperation and was one of the primary goals going into COP27 in 2022.

Tropical Island Nations

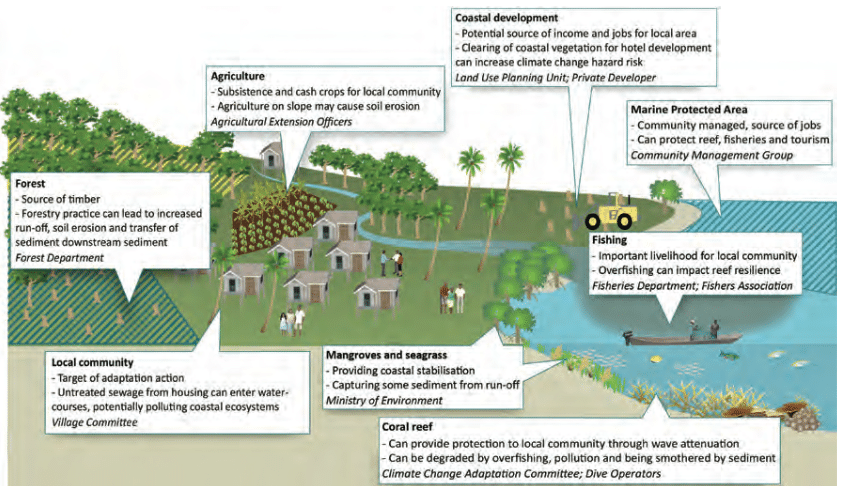

Island nations are among the first groups to feel significant, community-altering impacts from climate change. The leading risks of climate change for tropical islands are declining coral reefs from heat stress, damage from extreme storm events and rising sea levels. Potential adaptation to these risks includes:

- enhancing and maintaining natural ecosystem functions for storm protection, as coral reefs and mangrove forests reduce wave power and act as a natural break against storm surges,

- reducing human stressors on coral reefs by improving water quality, limiting destructive fishing practices and developing marine protected areas,

- adapting building codes to limit construction in at-risk coastal areas and

- implementing early warning systems for tsunamis and other extreme weather events.

While this list is nowhere near exhaustive, it outlines a few approaches the IPCC recommends for vulnerable island nations.

Coastal Regions

Coastal regions share many of the same threats as island nations, yet there is one stark difference – most coastal regions are parts of countries with larger protected inland areas. This difference gives coastal regions the domestic support of more protected areas for key services like food and water security.

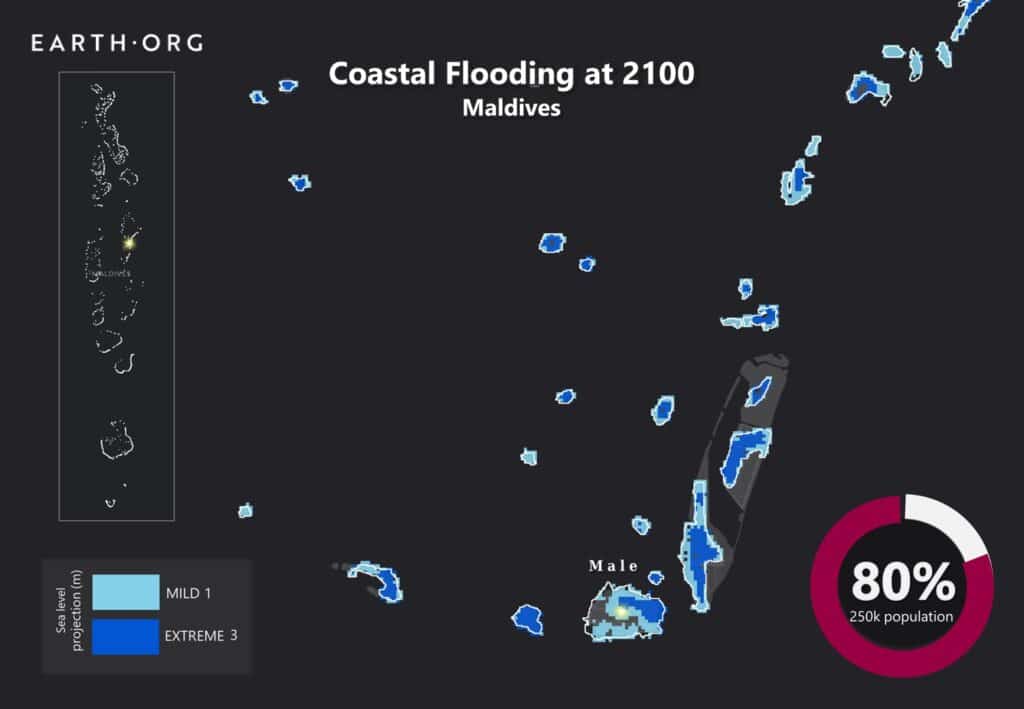

Additionally, while rising sea levels may force coastal communities to move, they can move inland. Some island nations don’t have this option and risk being completely underwater. For example, the average elevation of the Maldives is around 1.2 metres above sea level. Based on mid-level greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, scientists predict that 77% of the Maldives will be underwater by 2100.

Urban Areas

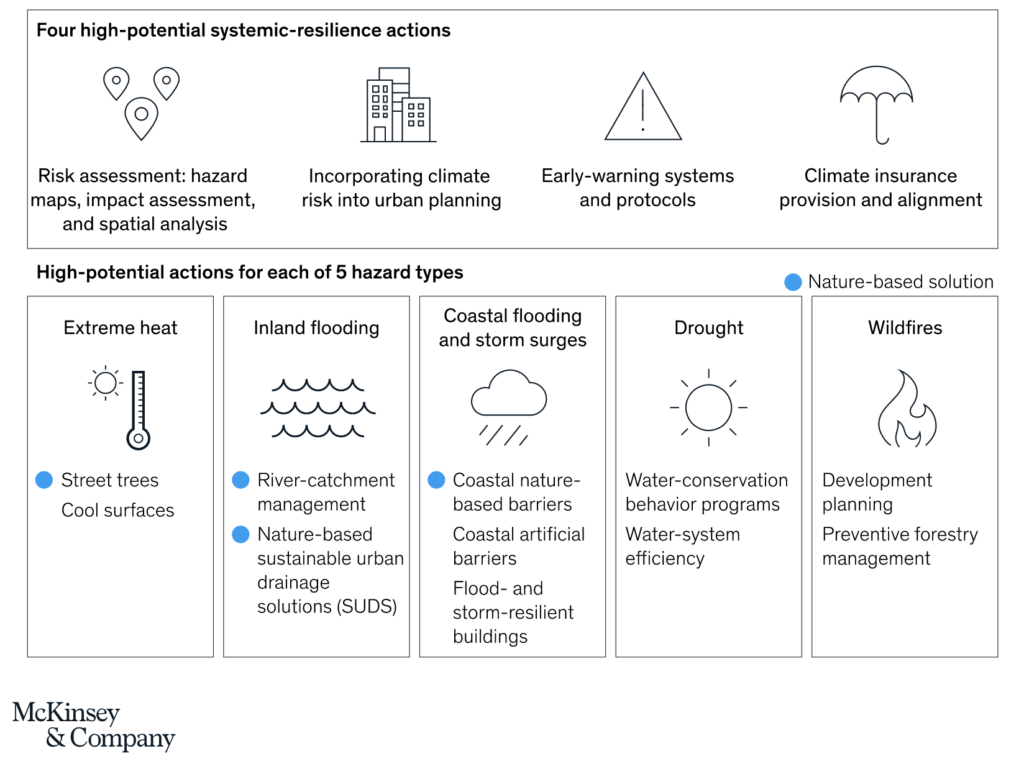

Over 50% of the world’s population lives in cities, with many people being highly vulnerable to climate change. The consulting firm McKinsey breaks up city adaptation into two stages: systemic-resilience actions and hazard-specific actions. Systemic activities increase the fundamental resilience of a city through widespread changes that are useful for any climate risk. Hazard-specific actions target the individual risk the city may face.

For example, systemic climate resilience, could be demonstrated through a city purchasing climate insurance, and hazard-specific actions could involve planting trees along streets to reduce ground-level heat. Combined, the two approaches develop an effective climate adaptation strategy.

Rural Areas

Rural communities rely heavily on climate-sensitive resources for their economic and social livelihoods. Climate change will dramatically alter these systems in the coming decades. Furthermore, rural areas lack economic diversity and typically rely on a few industries, like agriculture or forestry.

Agriculture is a cornerstone of human productivity, and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that by 2050, the world needs to produce 60% more food to meet global needs. At the same time, changing weather and temperature patterns, increasing rates of droughts and extreme weather events will disrupt agricultural systems worldwide. There will be similar trends in other natural resource-reliant industries.

As these rural-centric industries change, the associated communities may struggle to adapt. Due to high poverty rates, physical isolation and ageing populations, rural communities are vulnerable.

Adaptation strategies for these areas heavily focus on creating economic diversity in human societies. Meanwhile, developing the infrastructure needed for future climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts, like renewable energy facilities, is a great option. Additionally, increasing public services is essential for supporting rural areas with workers who spend a lot of their time outside. For developing countries, compensating rural groups to participate in climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts, like land conservation, is another option.

Developing Nations

Studies show that the lowest-income developing nations are the most heavily impacted by climate change. Additionally, they are also the least prepared to implement adaptation strategies. As a result, climate change adaptation requires the support of developed, wealthier nations. This is the major rallying cry of developing countries and is a central discussion at COP meetings.

For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts adaptation costs will be 0.25% of the global GDP. However, for around 50 of the world’s low-income countries, this rises to 1% of GDP for the next 10 years. Furthermore, the figure could exceed 20% of GDP for small island nations.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) lists health, hunger, water scarcity, education and refugee creation as the leading concerns for developing countries. First, developing nations heavily rely on agriculture, with 59% of their populations working in the sector. Changes in agricultural output and feasibility can cause food insecurity and economic downturn, which translate to less access to education and forced migration to already overburdened urban centres.

Second, increased heat, disease and extreme events will create numerous human health risks. For example, the warming will cause a 5% increase in the population at risk of contracting Malaria, which caused 619,000 deaths in 2021 alone.

Resilience-building activities supported by wealthy nations will limit the impacts to a level seen in the developed world, supporting developing communities and creating a more resilient global economy.

Examples of Climate Change Adaptation

There are many great examples of climate change adaptation projects, both currently implemented and under discussion. A few are:

- Community Work in Indonesia: In the Demak district of Java, the local community has restored a 20-km section of coastal mangroves, educated local fishermen on sustainable aquaculture and set caps on groundwater extraction. These activities provide 70,000 local people with the direct benefits of flood protection and increased aquaculture productivity. Added global benefits include additional carbon storage and biodiversity protection.

- Adapting to Extreme Heat in India: In 2010, more than 1,300 people died during a heatwave in Ahmedabad, India. In response, the city trained healthcare staff, painted roofs white to limit heat absorption and developed water distribution systems to limit the health risks of future extreme heat events. The plan was put to the test in 2015 during a similar heat wave in the city, and less than 20 people died.

- Natural Flood Protection in the Netherlands: The Netherlands’ government adopted a “room for the river” strategy along the Rhine River. The country removed dams, raised bridges, widened the river and added water catchment areas. The result is that the Rhine River can now carry 1,000 more cubic meters of water per second, reducing the risk of flooding.

These examples show that climate adaptation can be effectively implemented before and in response to extreme events. Additionally, awareness of climate adaptation is increasing worldwide, so new strategies are constantly under implementation.

Understanding the leading climate risks and their adaptation strategies is a great way to develop a large-scale climate strategy.

Climate Change Adaptation for Flooding

Increased flooding will be a significant climate change impact that the world has to adapt to. In its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), the IPCC acknowledges that there is “very high” confidence that global human systems will be impacted by inland and coastal flooding. Inland flooding primarily results from overflowing rivers, heavy rain and melting glaciers. Coastal flooding includes the same causes, as well as sea level rises, storm surges and cyclones.

Floods will lead to impacts across several human systems. First, it will increase the rate of waterborne diseases, like cholera, while at the same time disrupting health services. Second, it will adversely affect agricultural systems, leading to food insecurity and malnutrition. Third, it will damage existing infrastructure.

Adapting to floods is extremely important to limit these impacts. For example, the IPCC estimates that compared to 1.5oC warming, damage from floods will be two times higher at 2oC warming and 3.9 times higher at 3oC warming if there are no flood adaptation measures. Additionally, at 4oC warming, approximately 10% of all land cover will face risks of extremely high and low water levels.

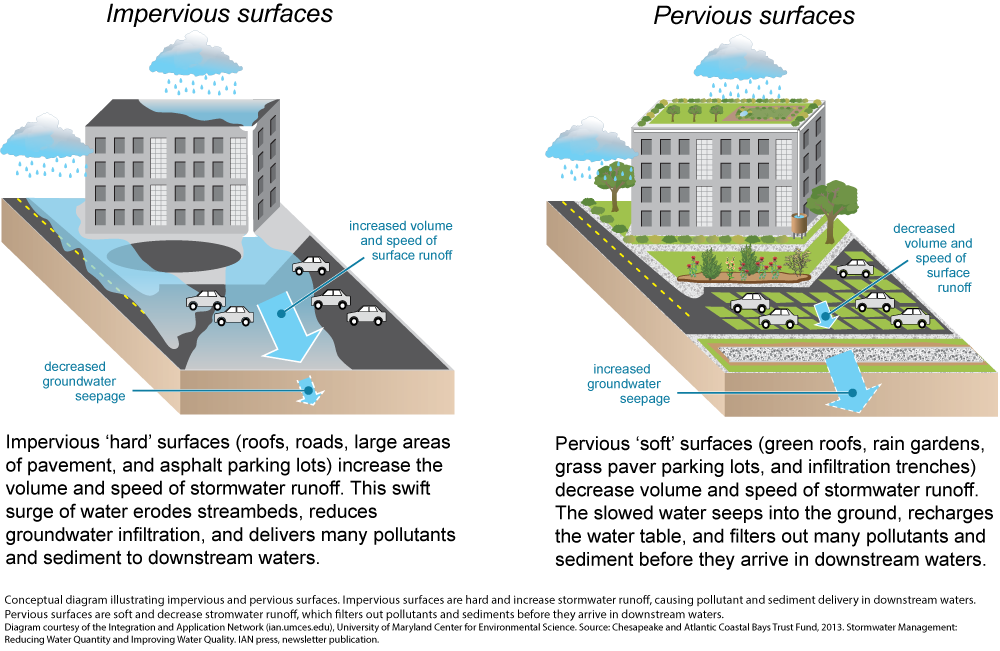

Adaptation measures rely on a combination of structural and non-structural strategies. Structural measures include options like levees to reduce water flow, improving stormwater control systems in non-permeable areas and ecosystem-based options. Ecosystem-based options mainly focus on enhancing natural water storage capacity through conserving wetlands, forests and rivers.

Non-structural strategies include implementing no-build zones in flood plains and high-risk areas, developing stormwater management strategies, educating the public and creating emergency response plans.

Unfortunately, the IPCC notes that the effectiveness of flood adaptation strategies declines with increased warming. Therefore, ongoing climate change mitigation efforts are crucial to effective long-term adaptation.

Climate Change Adaptation for Sea Level Rise

Rising sea levels are an inevitable impact of climate change. The IPCC notes that by 2050, 1 billion people will be exposed to risks associated with rising seas, which will continue to increase throughout the rest of the century. However, how fast and drastic the sea level rise occurs is heavily dependent on ongoing emissions, particularly in the second half of the century.

Sea level rise is caused by melting ice from glaciers and sea water expanding from rising temperatures. Impacts from rising temperatures and sea levels are twofold: inundation from high water levels and closer proximity to extreme weather events.

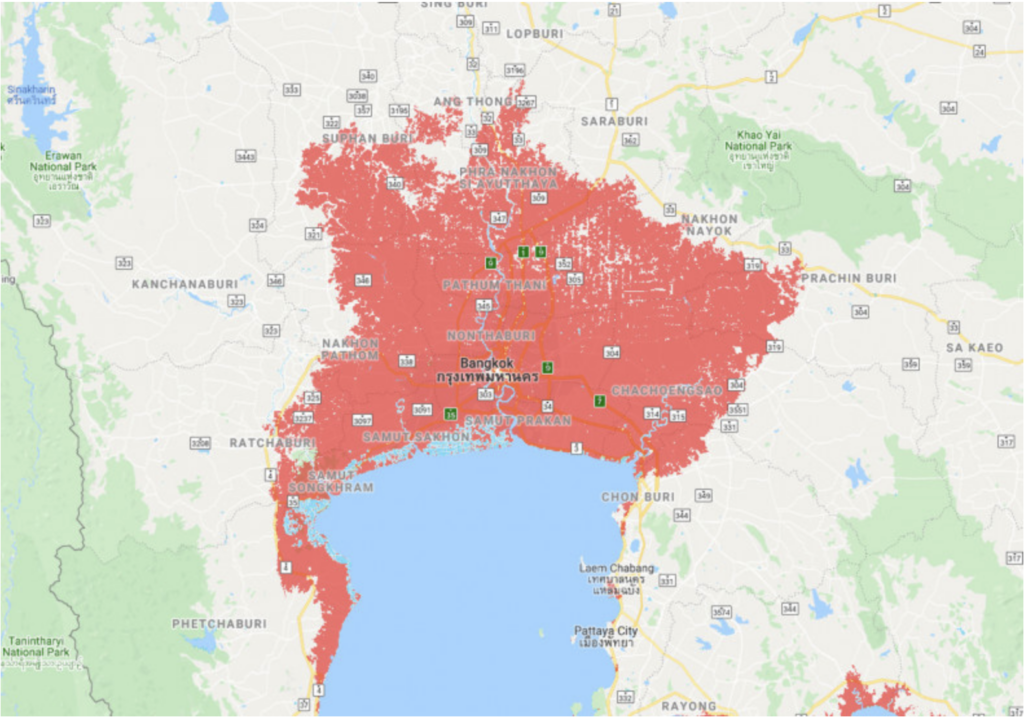

First, coastal and low-lying areas may become completely covered with water as ocean water levels increase, forcing existing communities to move. For example, the 2050 Climate Change Index ranked Bangkok, Thailand, as the world’s most vulnerable city to sea level rise.

More than 10% of its population (150 million people) are living in areas that will be underwater by 2050. This also translates to coastal freshwater aquifers, which may become tainted with salt water, leaving them unfit for drinking water or agriculture.

Second, higher water levels and higher temperatures mean coastal areas are more vulnerable to extreme weather events. Hurricanes, cyclones and tsunamis pose significant risks and lead to flooding.

By 2100, the cost of global assets located within coastal floodplains will be between USD 7.9 trillion and USD 12.7 trillion based on the RCP 4.5 global warming scenario (global emissions peaking in 2040 and then declining).

Sea Level Rise: Adaptation Approaches

There are five options for adapting existing infrastructure to higher sea levels: protect, accommodate, advance, retreat and retreat with ecosystem-based adaptation.

- Protect: Develop engineering controls, like sea walls and levees, to stop water from advancing.

- Accommodate: Allow structures to function with the rising sea level, like elevating structures or purchasing insurance.

- Advance: Build a buffer into the ocean to increase the land area between the ocean and the structure.

- Retreat: Move structures away from the ocean.

- Retreat with Ecosystem-Based Adaptation: Move structures away from the ocean and develop natural strategies to reduce extreme weather, like planting mangrove trees.

In addition to these options, climate information, long-term development planning that considers future sea level rises and government programs that will move people out of high-risk areas are critical strategies for adaptation.

Climate Change Adaptation for Extreme Heat

Global average temperatures have increased by over 1oC in the last century, and the number of extreme heat events and record high temperatures are rising. In the United States, the frequency of heatwaves has tripled since the 1960s, and the IPCC expects a similar trend across the world. Use of fossil fuels is the main culprit.

This is causing a parallel uptick in heat-related deaths, with a 74% increase between 1980 and 2016. A 2001 study found that 5 million deaths yearly are linked to extreme hot or cold temperatures.

Additionally, extreme heat leads to a host of societal and environmental degradation and infrastructure problems, including:

- damage to roads, energy systems and heat-sensitive infrastructure,

- additional energy used for cooling, stressing electrical grids,

- livestock damage or death and

- increased likelihood of natural disasters, like droughts and wildfires.

Extreme Heat: Adaptation Approaches

Adaptation relies on limiting ground-level heat, staying inside on days with extreme heat and developing efficient cooling methods. Extreme heat is a major concern for urban centres where the heat island effect can raise temperatures by over 3oC compared to green areas.

Increasing greenery in cities by lining streets with trees and adding landscaping can help reduce ground-level temperatures. Additionally, upgrading surfaces to reflect heat instead of absorbing it, like painting roofs white, can dramatically affect temperatures.

Meanwhile, other options include educating vulnerable populations on heat preparedness, opening public cooling centres for low-income groups and developing early warning systems. Finally, governments can update their energy and water infrastructure to handle extreme heat events.

Climate Change Adaptation for Agriculture

Climate change can affect agriculture in multiple ways – from droughts and flooding to pests and diseases. Agriculture is a critical industry for the world and plays a central role in many local, regional, and national economies. Due to the impacts of climate change, global agricultural output will likely decline. This is backed up by a 2021 study that found global farming productivity is already 21% lower than it could have been without climate change.

However, with global warming, agriculture yield will not decline gradually. It will be punctuated by shifts in where and what type of agriculture is viable in warmer climate. Some regions may become too hot, while others may become too wet or cold. For example, a recent study by NASA predicted that global corn yields will decline by 24% by 2030, yet wheat will see an increase of 17% during the same period.

This will be problematic for regions that rely heavily on agriculture for jobs and have the infrastructure in place for production. Shifts in global patterns will force people to migrate to stay in the industry, forcing them to start production from the ground up. This could increase the global rate of food insecurity and malnutrition by 20% by 2050.

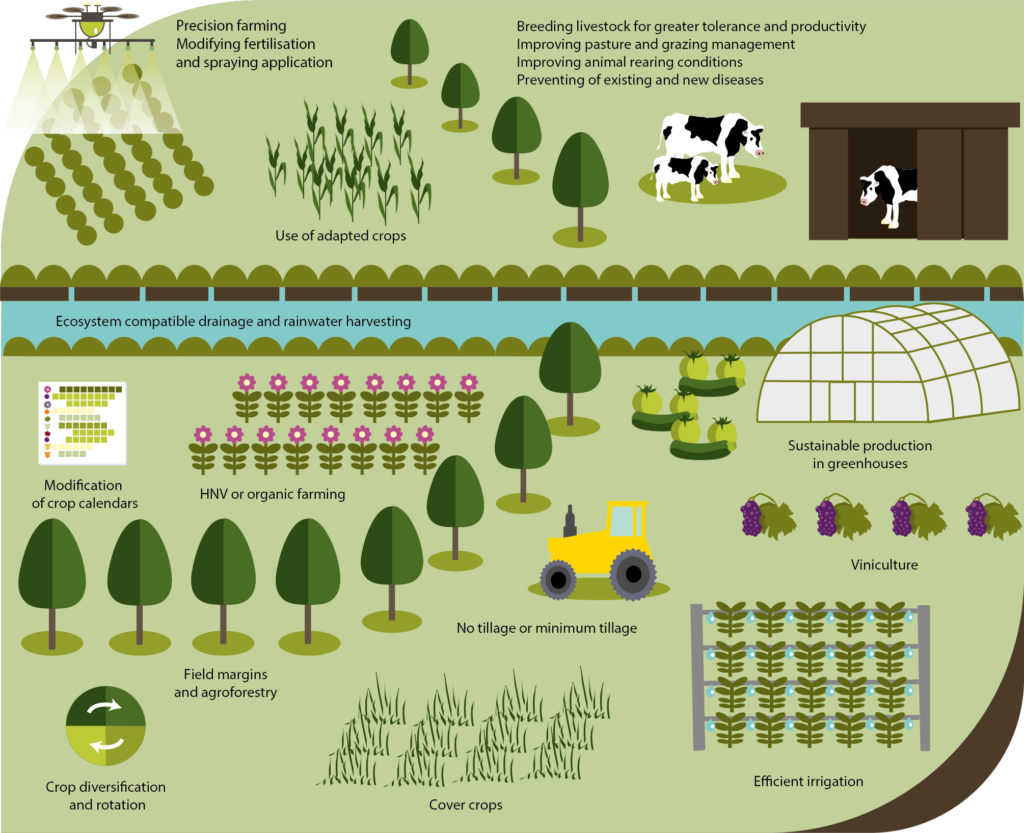

Agriculture: Adaptation Approaches

Agricultural adaptation is applied on five scales: plant, field, farm, landscape and regional. Each scale has multiple adaptation options, but the most common for each are:

- Plant scale: by crop breeding to utilise favourable attributes. In most cases, this will be drought tolerance or pest resistance.

- Field scale: by improving soil health, which increases crop resiliency and yields. This can be achieved through planting cover crops and reducing tilling.

- Farm scale: by extending crop rotations, which can help break standard pest and disease cycles.

- Landscape scale: by shifting to different, more resilient crops when the adaptive capacity of the field is maximised.

- Regional scale: by implementing land use changes when agricultural land is no longer viable. This could be by switching fields to floodplains or community parks and compensating farmers for the ecosystem services they provide.

Adapting agricultural practices to work within the changing environment is critical to developing a resilient global agricultural system in the coming decades.

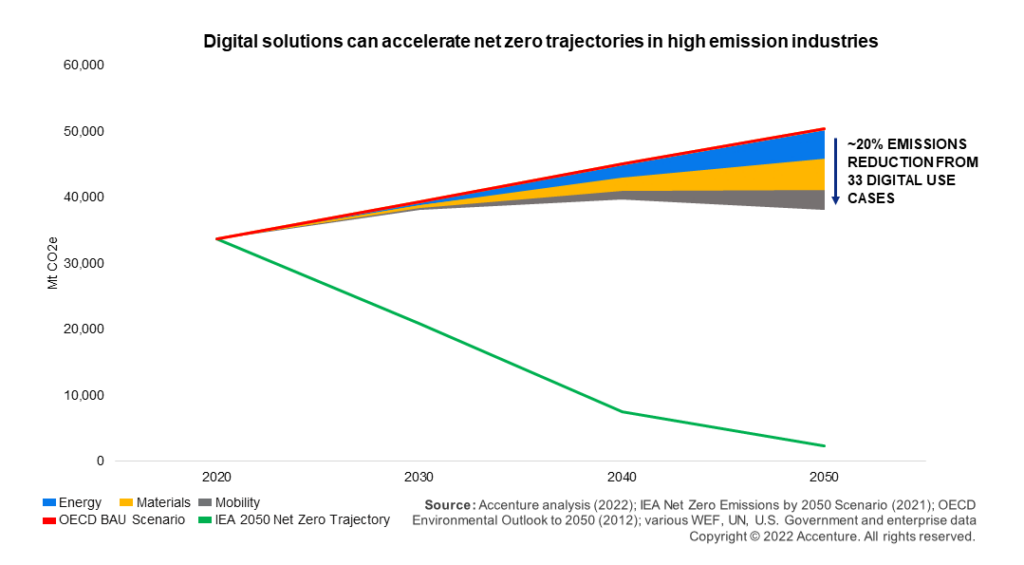

Technology Will Boost Global Climate Adaptation

For example, work by Accenture and the WEF finds that digital technology scaled in the energy, materials and mobility sectors can reduce global emissions by 20% by 2050. There will be a similar trend in adaptation, where technology is critical to collecting and analysing large datasets to prepare for climate impacts.

What Are Examples of Climate Adaptation Technologies?

Climate adaptation technologies take many forms: supercomputing, new forms of infrastructure, advancements in crop genetics, vaccines and more. However, for the sake of this discussion, we are focusing on three specific technologies that can revolutionise adaptation.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI can analyse large, complex datasets and make predictions, which is invaluable for immediate and long-term hazard forecasting. AI can play a central role in adaptation to almost all climate impacts, from improving disaster early warning systems to informing regional no-build zones and development plans.

- Natural Resource Insurance: Providing insurance for existing natural resources that are under the threat of damage from extreme weather events. This protects the ecosystem services that resources provide and gives the local community economic and social opportunities. The Mesoamerican Reef (MAR) Insurance Program is one of the first coral reef insurance programs. In 2022, it provided a USD 175,000 payout to facilitate restoration activities for the Turneffe Atoll in Belize after Hurricane Lisa.

- Sea Water Desalination: Heat, droughts, rising sea levels and extreme weather events will severely impact water security and access. Developing new approaches for harvesting water for drinking and agriculture is crucial. Currently, desalination has many drawbacks, making it only viable in specific use cases. However, as the technology advances, it can play an important role in diversifying water access for communities worldwide.

We Need to Accelerate Climate Change Adaptation Efforts

A majority of the world’s population will feel the effects of a climate hazard by 2050. Rapid climate change adaptation has the potential to save millions of lives and slow climate migrations that have already topped 100 million people. Additionally, climate crisis and adaptation responses will protect the livelihoods of local communities and provide pathways to capitalise on environmental changes for future generations.

This is particularly crucial for the developing world, which needs funding from advanced countries to meet critical adaptation milestones. Without funding, these countries and small island developing states (SIDS) in particular, will feel catastrophic damage from climate change. SIDS in the Caribbean are projected to have a GDP loss of 5% per year by 2025, which will increase to 20% per year by 2100 without climate change adaptation measures in use.

Currently, global financial assets exceed USD 379 trillion. Less than 1% of this is enough to achieve all of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, and 0.25% will eliminate the climate adaptation gap. The funding and technology are available, yet global cooperation is not. It’s time for governments, companies and communities to follow the science and fund the adaptation that the world needs.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.