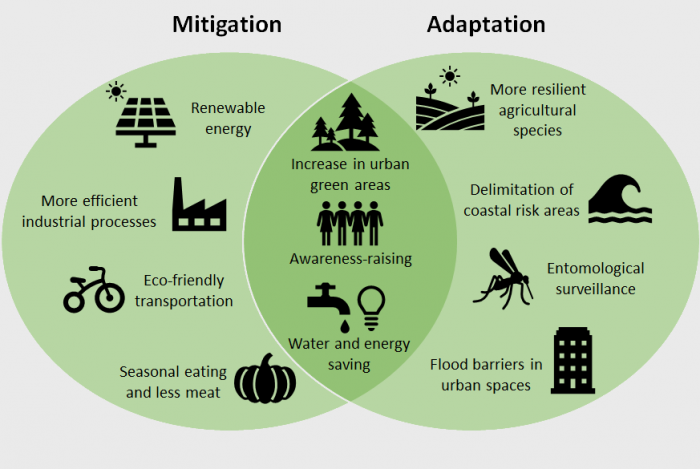

When dealing with climate change policy and action, the ideas of climate change adaptation versus mitigation are often used in similar contexts. However, both terms should not be lumped together, as they define different types of actions to combat climate change.

What Is Climate Change Mitigation?

Within the context of the Paris Agreement, climate change mitigation refers to actions that limit the causes of climate change to keep the global temperature rise below 2°C.

What Is Climate Change Adaptation?

Climate adaptation refers to the ability of communities to react and adjust to climate change impacts.

Both mitigation and adaptation are critical to protecting global communities and will define the world in the coming decades.

How Do Mitigation and Adaptation Work Together to Fight Global Warming?

Climate change mitigation and adaptation don’t work in isolation to deal with global warming and changing climate. Instead, adaptation and mitigation are complementary actions within the same broader shift.

“You shouldn’t be choosing between adaptation and mitigation”, says the Minister of International Cooperation of Egypt Rania Al-Mashat.

We need climate change adaptation and mitigation actions to build a liveable, resilient world. Mitigation will limit the future impacts of climate change, and adaptation will help the world live with those changes. If mitigation or adaptation is inadequate, we either end up with communities that can’t thrive even with inevitable minor climate impacts or expected future climate impacts that are too extreme to adapt to.

Adaptation and Mitigation Are Not Always Equal

In theory, this means that national governments should address adaptation and mitigation equally. However, factors such as vulnerability, fair share climate contributions and economic development may tip the scale in one direction.

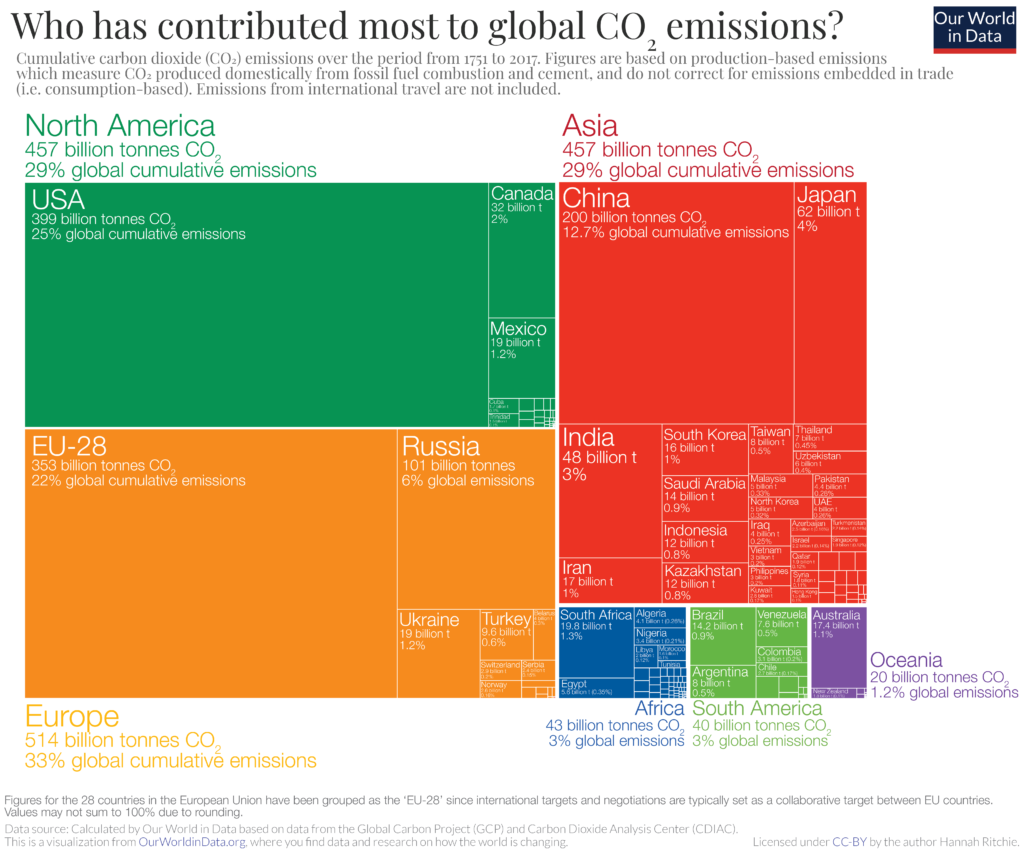

For example, the United States, which has contributed over 400 billion tonnes of historic carbon emissions, or roughly a quarter of cumulative global greenhouse gas emissions, has a larger “fair share” of contributions towards global mitigation efforts than other countries. As such, the United States has a responsibility and the economic capacity to mitigate climate change, while focusing less on adaptation.

On the other hand, Indonesia must focus on both at relatively equal levels. The country is vulnerable to climate change but is also heavily reliant on fossil fuels, which exacerbates these issues.

A smaller nation like Tuvalu will focus primarily on adaptation, as it is a low-lying island nation that faces the near-term threat of sea level rise. Then, as the country develops its adaptation solutions and economy, it will seek opportunities to mitigate climate change by adopting sustainable solutions.

What Are Some Examples of Adaptation and Mitigation?

Mitigation relates to the actions that cause climate change, such as heat trapping greenhouse gases. Meanwhile, anything that aims to reduce carbon dioxide emissions is mitigation. For example, changes in policy to favour renewable energy, decrease the use of fossil fuels and accelerate the transition to low-carbon technologies would all fall into mitigation.

Climate change’s impacts are diverse, so adaptation is different for each community. In disaster-prone areas, adaptation could take place by improving emergency response infrastructure. However, countries with limited water resources could seek to improve their water management.

Long-term Adaptation in Tuvalu

An interesting case study for climate change adaptation is Tuvalu’s Long-term Adaptation Plan (L-TAP). A small low-lying atoll nation, Tuvalu is one of several countries at risk due to sea level rise.

According to the United Nations Development Program, “By 2050, it is estimated that half the land area of the capital will become flooded by tidal waters.” It adds, “By 2100, 95% of land will be flooded by routine high tides.”

One of the main components of L-TAP is developing a 3.6 square km area of raised land. The island nation’s citizens and infrastructure will slowly relocate to this area as ocean levels rise. Further development with climate-resilient infrastructure like renewable energy, a sustainable water supply and local food production will enhance resiliency.

What Are the Differences Between Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Costs?

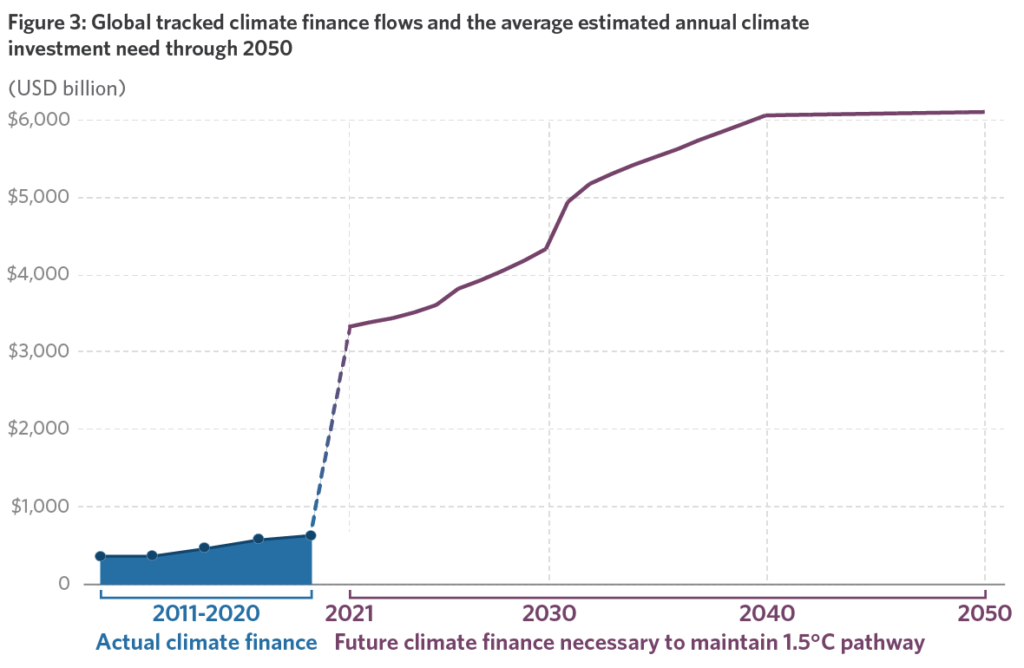

The costs for both adaptation and mitigation are high. However, both actions develop new pathways for carrying out socioeconomic processes that require innovative solutions, new initiatives and the proper funding to maintain them.

However, the capital needed to carry out climate adaptation and mitigation benefit high-performing economies. This leaves developing and vulnerable countries with fewer options to develop their own strategies.

“Every USD 1 invested in adaptation could yield up to USD 10 in net economic benefits, depending on the activity,” explains finance and development writer Adam Behsudi. The writer goes on to state that adaptation measures “save money in the long run” but require up-front costs that can be a burden for developing countries. He adds, “Some are caught in a vicious circle: limited fiscal space hinders their ability to adapt to climate change and worsening climate shocks raise their risk premiums, increasing the cost of borrowing in global financial markets.”

Adaptation and Mitigation Funding Pathways

As such, there are many new financial initiatives in the pipeline of international policy to meet the financial needs of climate-vulnerable communities and developing countries unable to finance their adaptation or mitigation needs.

The Loss and Damage fund, the Bridgetown Initiative and the – so far unmet – “USD 100 billion yearly” pledge from developed nations are just some of the opportunities. Additionally, with the climate change adaptation market estimated at USD 2 trillion, the private sector will continue to help develop crucial adaptation technologies in the coming decades.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.