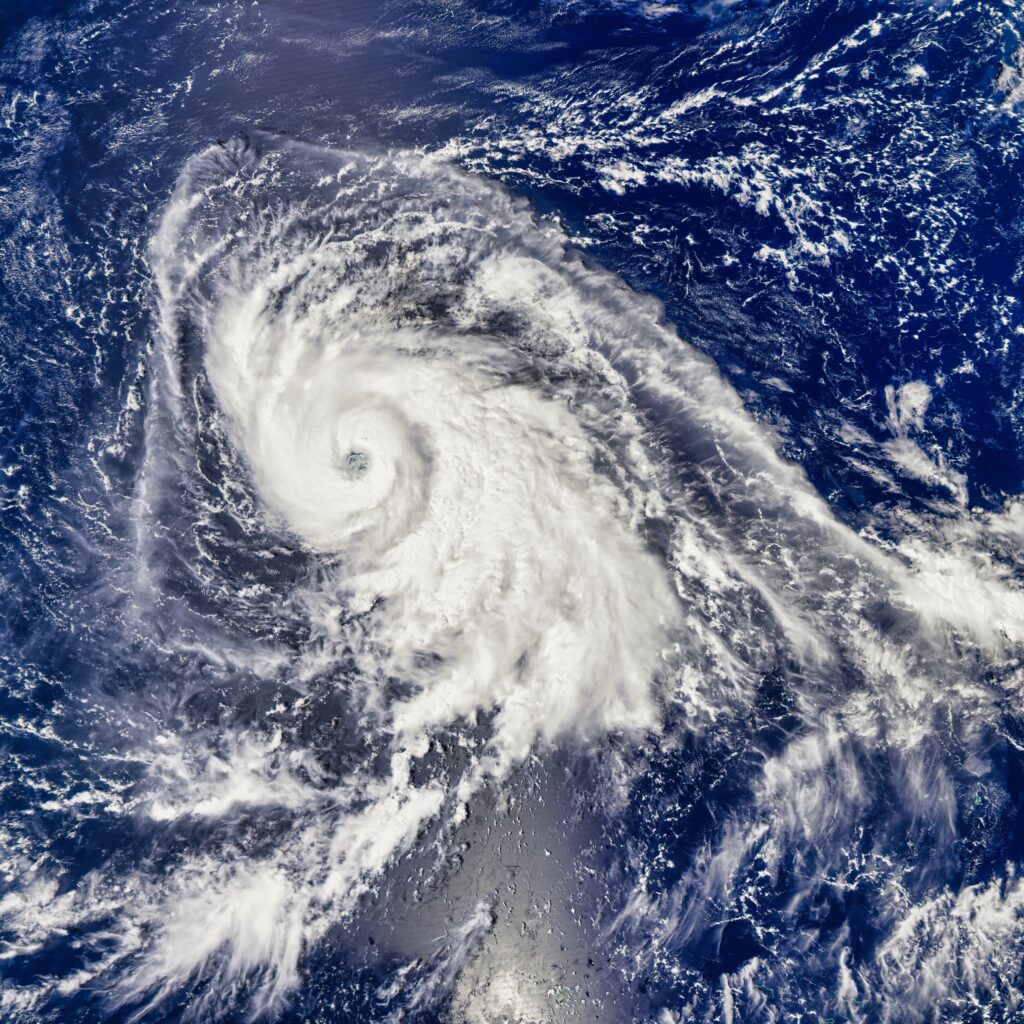

In December 2021, Super Typhoon Rai, known locally as Super Typhoon Odette, made landfall in the southern Philippines, tearing through major population centres and tourist areas in the Visayas islands and bringing devastating rains, winds and storm surges.

The Category 5 storm led to at least 407 deaths, damaged or destroyed 1.5 million homes and caused more than USD 1 billion in damage. It became the country’s second-costliest typhoon after Super Typhoon Haiyan, which caused historic damage in 2013 when it slammed the country’s easternmost islands.

The next year, in September 2022, Super Typhoon Noru hit the Philippines after intensifying at unusually fast speeds, leading to more deaths and evacuations. Days later, Hurricane Ian hit the coast of Florida after knocking out Cuba’s power grid, becoming the fifth-strongest hurricane ever to hit the contiguous United States.

Climate Change Impacts on Typhoon Season

Researchers have been attempting to determine the role of human-caused climate change impacts on typhoon season and in the recent uptick in storms of uncommon severity.

Studies show that while tropical cyclone frequency is the same – they’re occurring at the same rate as the pre-industrial era, before humans began emitting greenhouse gases. But tropical cyclone intensity is higher: building their strength faster, travelling slower and leaving colossal damage in their wake.

That’s led to a growing consensus that, in a warming climate, future tropical storms may not increase in frequency, but they will continue becoming more destructive.

How Does Climate Change Affect Hurricanes and Tropical Cyclones?

After the Category 5 Super Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines in 2013, a report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) showed that the storm became stronger due to an increase in ocean heat content, along with sea level rise – the naturally occurring phenomena exacerbated by human-caused climate change.

The story of Haiyan, which killed at least 6,300 people and caused USD 3 billion in damage, is a cautionary tale of how global warming fuels tropical cyclones in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Landfalling Category 4 and 5 typhoons in East and Southeast Asia have doubled or tripled in number since the late 1970s, according to a 2016 study.

The study, published in Nature Geoscience, also found that intense storms striking these countries have intensified by 12-15% due to warming sea surface temperatures in the region. As ocean surfaces keep getting hotter, typhoons hitting China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan will likely intensify even further, the authors said.

When the water beneath the ocean’s surface is colder, it also acts as a coolant as storms build up, restraining the speed and severity of their growth.

Conversely, hotter oceans, combined with rising sea levels, act as a Petri dish for storms to rapidly gain strength and barrel into land masses at full potency.

Are Stronger Typhoons Caused by Climate Change?

When Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas in 2017, it sat in place for three days and relentlessly battered the state’s Gulf Coast, rather than moving on and dissipating. A study in Environmental Research Letters later concluded this unusual tropical storm pattern was made three times more likely by human-caused climate change.

“Harvey was more intense because of today’s climate, and storms like Harvey are more likely in today’s climate,” Antonia Sebastian, a researcher with Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters Center and co-author of the study, told Scientific American.

Millions of Americans on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts have noticed changes in hurricane patterns. Storms that petered out upon striking land now barrel up and down coasts, sometimes forging unexpected paths that confound meteorologists.

And while improvements in disaster response have slashed the number of deaths caused by hurricanes and typhoons, the storms are causing far more property damage. In the US, weather and climate disasters caused USD 788 billion in damage from 2017 to 2022 – about one-third of the entire total from 1980 until 2022.

These stronger storms are beginning to force people to rethink settling on coastlines – areas prone to tropical cyclones. But, in many Asian countries, inhabitants have little choice.

In the Philippines, land occupied by 6.8 million people could be underwater within 30 years as sea levels continue to rise, according to a study by Climate Central – which based its analysis on a conservative scenario of climate change.

With around 55% of the country’s 114 million people live in coastal areas at sea level, leaving them prone to typhoons, of which the country sees around 20 in an average year.

Super Typhoon Haiyan also displaced 5 million people, many of whom resettled elsewhere instead of returning to their homes. And experts believe that worsening storms in Asian countries are bound to create new waves of climate migrants, both internally and for other countries.

Nick Aspinwall

Journalist, New York

Nick Aspinwall is a journalist based in New York. He was previously based in Taipei and Manila. He reports on migration, the environment, labor rights, and the human consequences of geopolitics. Nick’s work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Vice, Al Jazeera, The Nation, Foreign Policy, Reuters, The New Humanitarian and many more. When he’s not reporting, he’s probably on a diving boat or getting lost in a mountain range.

Nick Aspinwall is a journalist based in New York. He was previously based in Taipei and Manila. He reports on migration, the environment, labor rights, and the human consequences of geopolitics. Nick’s work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, Vice, Al Jazeera, The Nation, Foreign Policy, Reuters, The New Humanitarian and many more. When he’s not reporting, he’s probably on a diving boat or getting lost in a mountain range.