The science is conclusive: climate change is already and will continue to disrupt the natural and socioeconomic systems we depend on. Climate change adaptation is integral to our collective future, and whatever the climate change adaptation costs, it’s necessary for survival.

However, there is a significant funding gap for climate adaptation programs. This is highlighted by developing nations on the front lines of global warming that have the least financial capacity to adapt. Lagging efforts by decision-makers in the private and public sectors will have direct, consequential implications for these communities.

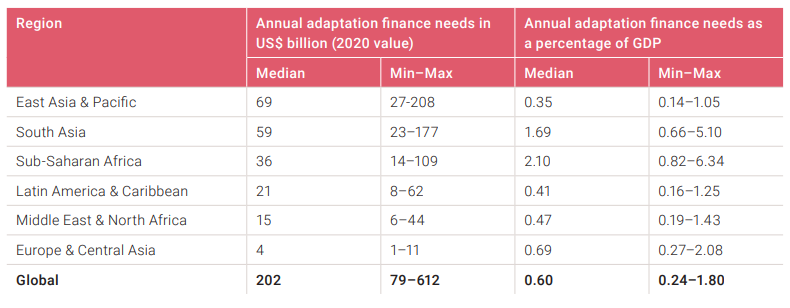

“International adaptation finance flows to developing countries are five to 10 times below estimated needs, and the gap is widening,” notes the United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) 2022 Adaptation Gap Report. “Estimated annual adaptation needs are USD 160-340 billion by 2030 and USD 315-565 billion by 2050,” it says.

So, why exactly is there such a large gap, and why is adaptation so important?

What Is the Cost of Climate Adaptation?

As noted in the Adaptation Gap Report, there is a need for over USD 565 billion by 2050 to develop adaptation measures. However, the cost of climate change adaptation is likely higher, as the compounding damage of climate change exacerbates the already stressed infrastructure of vulnerable nations.

Inaction on Climate Finance

Every year that there is inaction on climate finance, the cost to adapt increases. However, the cost of inaction will also affect the course that climate change takes, increasing the severity of its impacts.

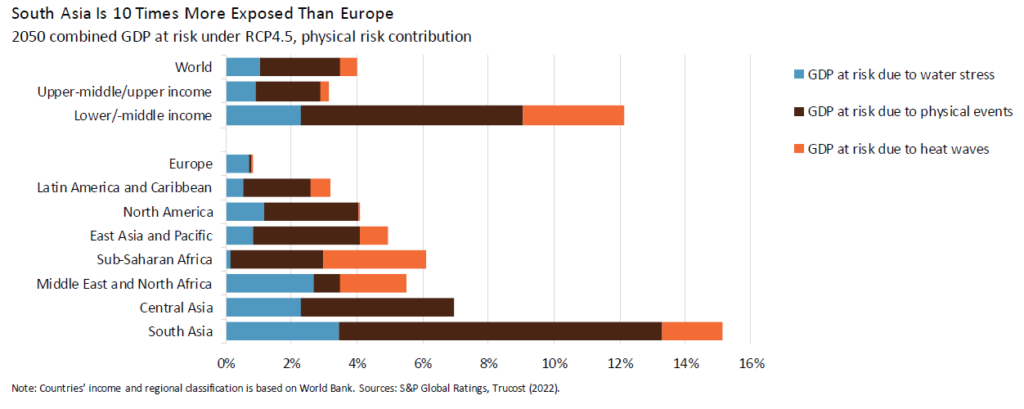

A 2014 Asian Development Bank (ADB) report warned of the economic outlook across Asia should climate change continue unabated. It found that Asia could find itself with a regional GDP loss of 1.8% by 2050, which could reach 8.8% by 2100.

However, these estimates have increased in recent years. A 2022 report by S&P Global found that unabated climate change will cause a 10-18% GDP loss in South Asia by 2050. Swiss Re Group, a leading reinsurance provider, found ASEAN markets could lose up to 37% of their GDP by 2048.

As climate change progresses, mitigation and adaptation become harder, and expected losses become larger.

Climate Adaptation Is a Good Investment

Investing in adaptation is investing in the future-proofing and resilience-building of at-risk communities. Adaptation will enable vulnerable countries to spend less money on recovering from climate impacts, improving their long-term socioeconomic health. This will ensure that national economies are less vulnerable to external shocks while developing local industries.

This translates to a favourable cost-benefit ratio of between 2:1 to 10:1. The World Economic Forum (WEF) found that USD 1.8 trillion in climate adaptation funding could lead to USD 7.1 trillion in benefits. Adaptation is a cost-effective and efficient way to combat climate change.

What Are Climate Change Adaptation Costs for Developing Countries?

Due to the variable impacts by region and each nation’s unique infrastructure systems, adaptation needs differ by country.

For example, developing countries like Tuvalu or Tokelau in the Pacific are low-lying atolls. Sea-level rise, cyclones, erosion and seawater encroachment into aquifers are the primary concerns. Some adaptation methods could include building seawalls, strengthening the shoreline, improving water governance and improving emergency services. These solutions would differ from countries like Kenya, where drought is a major issue, or Bangladesh, where the land is prone to floods.

There is no one-size-fits-all adaptation solution, so the cost of implementing adaptation is generally high. However, these up-front costs will provide services and improvements for local communities, improving their quality of life and providing a solid return on investment.

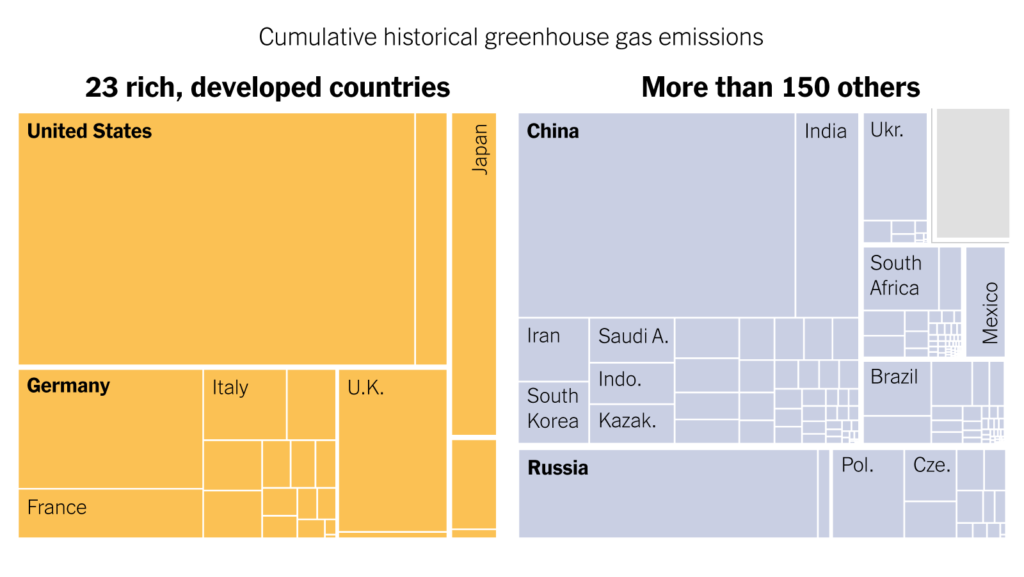

The crux of the issue remains in the lack of available funding for vulnerable or developing countries. Developed countries have the capital to finance adaptation but are not sharing it – as repeated climate negotiations have shown.

On the other hand, developing countries face climate risks and impacts but have limited opportunities to take them on or adapt. Therefore, they have to finance their own adaptation costs for a crisis they had little part in creating.

There Is Still a Significant Adaptation Financing Gap

Outside of the USD 565 billion by 2050 funding gap presented by UN Environment Programme (UNEP), promises made on the global stage have also not been kept.

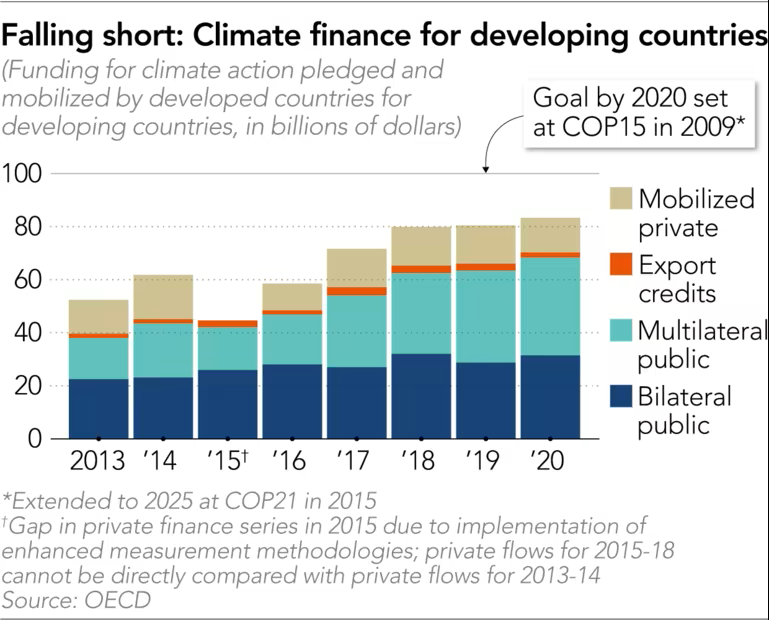

Ahead of the 2021 UN Climate Summit (COP26), the existing USD 100 billion per year funding commitment from developed nations for climate-vulnerable countries was still not met.

During the summit’s opening, Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley criticised the inaction on display. “Our people are watching and taking note. On finance, we are 20 billion dollars short of the 100 [billion pledged] and this commitment might only be met in 2023. On adaptation – adaptation finance remains only 25% – not the 50:50 split needed given the warming that is already taking place,” she said.

“Climate finance to frontline SIDS [Small Island Developing States] declined by 25% in 2019. Failure to provide this critical finance and that of loss and damage is measured in lives and livelihoods being lost in our communities. It is immoral and unjust,” she added.

Still today, the funding gap for the pledge is still apparent, and while there has been some loosening of climate finances, the amount remains too little to have the immediate impact needed.

Eric Koons

Writer, United States

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.

Eric is a passionate environmental advocate that believes renewable energy is a key piece in meeting the world’s growing energy demands. He received an environmental science degree from the University of California and has worked to promote environmentally and socially sustainable practices since. Eric has worked with leading environmental organisations, such as World Resources Institute and Hitachi ABB Power Grids.