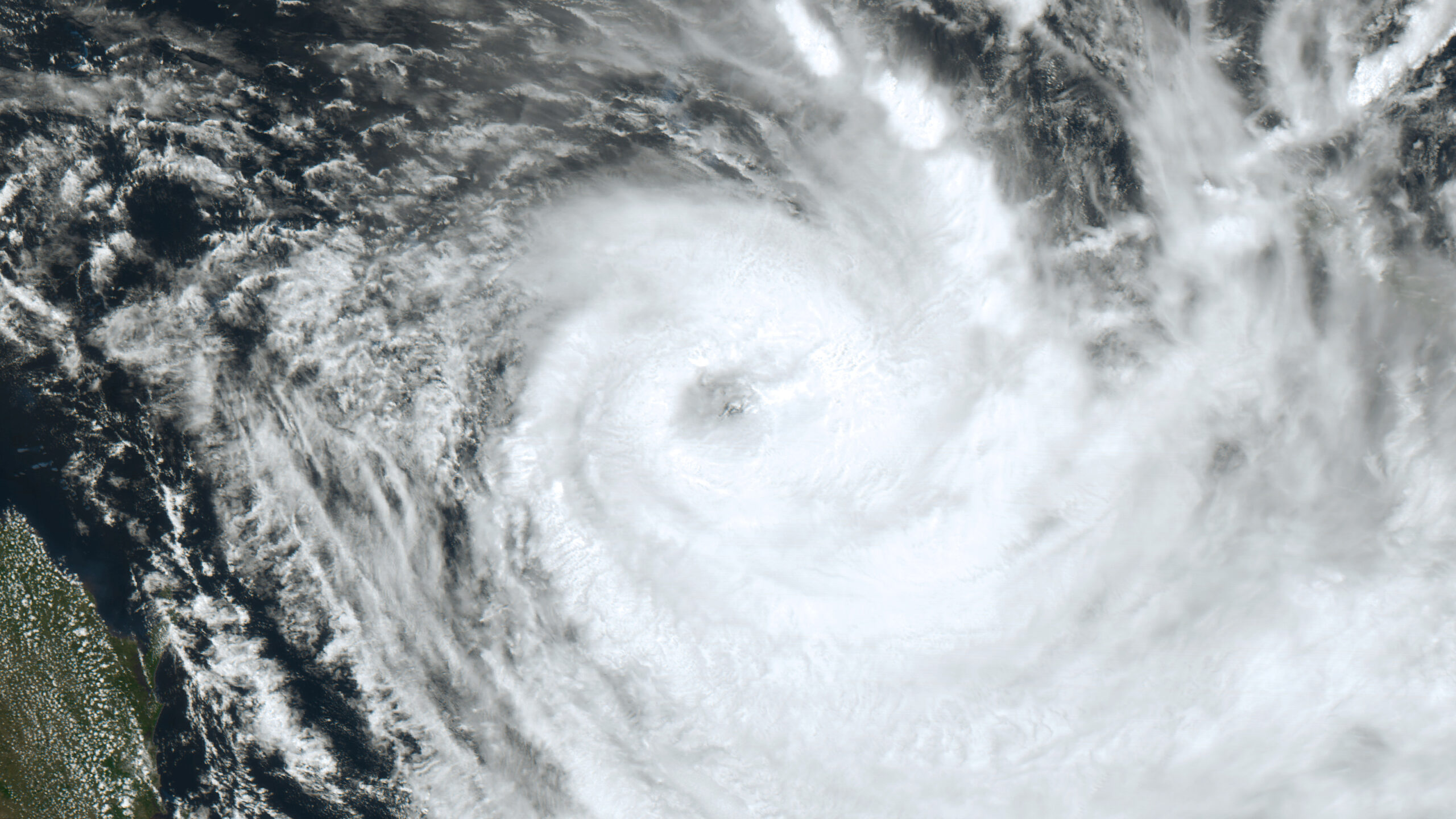

In mid-February 2023, devastating flooding in New Zealand from Cyclone Gabrielle destroyed homes, bridges and roads, leading to the tragic loss of at least 11 lives and billions of dollars in damage. As the torrential rains began to ease, Prime Minister Chris Hipkins named it the worst storm to hit this century. “The severity and the damage that we are seeing has not been experienced in a generation,” Hipkins said.

Yet, Cyclone Gabrielle occurred just two weeks after record rainfall caused severe flooding in Auckland and Northland, damaging thousands of homes and killing four people. At the time, the flooding was named as the most destructive climate-related event in New Zealand’s history.

There is general agreement in the scientific community that destructive weather patterns, like Cyclone Gabrielle, are linked to climate change. Furthermore, it is more likely than not that these extreme events are expected to intensify as the climate continues to heat. A prudent question arises: how can at-risk countries better prepare for extreme weather events to come?

How Common Are Cyclones in New Zealand?

Tropical cyclones are not uncommon in New Zealand. Around 10 cyclones will form in the South Pacific tropics each summer, and on average, at least one travels south and impacts the island nation.

However, while most cyclones are fleeting, a “blocking” high-pressure system caused Cyclone Gabrielle to stall and run aground to the east of New Zealand. Between February 13 and 14, a colossal amount of rain fell on the Hawke’s Bay and Gisborne regions — exceeding 20 mm an hour for more than six hours in some areas. The result was extreme and unprecedented damage, with the “epicentre of devastation” in Te Matau-a-Māui (Gisborne) and Te Tairāwhiti (Hawke’s Bay), on the east coast of Te Ika-a-Māui (North Island).

The severity of this particular cyclone meant that officials declared a national state of emergency – only the third such declaration in the country’s history.

The Devastating Impacts of Tropical Cyclone Gabrielle

The intense and prolonged rains from Cyclone Gabrielle caused rivers to rise rapidly, leading to devastating flooding in both rural and urban communities. Storm surges and landslides also battered the New Zealand, forcing evacuations, stranding people on rooftops, and destroying crops.

The downpours caused extensive damage to lifeline infrastructure, including “roads, bridges, electricity access, communication access and even access to fresh water”, noted Dr. Luke Harrington, a senior lecturer at the University of Waikato.

At the peak of the storm, 225,000 homes were without power in the cyclone affected areas. Thousands of people were unreachable for several days due to road blockages and telecommunications outages. Overall, nearly one-third of New Zealand’s population of five million people was affected.

The government described the significant damage caused by Cyclone Gabrielle as comparable to the 2011 Waitaha (Canterbury) earthquakes. Cyclone Gabrielle has now topped the tables as the costliest tropical cyclone on record in the Southern Hemisphere, estimated at more than USD 8 billion.

Climate Change is Fuelling Tropical Cyclones Like Gabrielle

In the weeks following the cyclone, World Weather Attribution (WWA) published a study showing that heavy rainfall events, like those seen during Cyclone Gabrielle, now produce around 30% more rain than before humans impacted the climate. Similar events also occur in the region about four times more often than previously.

Dr. Friederike Otto, the study’s leader, says climate change undoubtedly influenced the rainfall from Cyclone Gabrielle. “Weather observations in the region show exactly what we expect from physics, which is that a warmer atmosphere accumulates more water and increases the frequency and intensity of downpours,” said Otto. She reiterated the warning that in a heating world, more extreme events are likely.

Sam Dean, a principal scientist at the New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and a co-author of the study, agrees. “I have no doubt whatsoever in my mind with my experience of my life as a climate scientist that climate change has influenced the event,” he said in reference to Cyclone Gabrielle. Dean added that the study “contributes to a wealth of evidence” that highlighted adaptation to flood risk as one of the great challenges facing not just New Zealand but the globe.

New Zealand’s Minister for Climate Change James Shaw also recognised the role of climate change in fuelling Cyclone Gabrielle’s impacts. While delivering an impassioned speech in parliament, Shaw said, “I don’t think I’ve ever felt as sad or as angry about the lost decades that we spent bickering and arguing about whether climate change was real or not… because it is clearly here now, and if we do not act, it will get worse.”

Preparing for Future Cyclones and Floods

As climate change drives more frequent and intense disasters, community-based approaches can help build resilience against future events, according to Associate Professor at the University of Newcastle Dr. Iftekhar Ahmed. He says that volunteers visiting vulnerable homes to check on preparedness and provide evacuation support during floods are paramount.

This is unlikely to solve the issues of how cities across the globe have developed without long-term resilience from extreme weather events in mind. Ahmed says that there is a fundamental need to revisit how cities grow, with food resilience, green areas, drainage and transport playing important roles.

Lessons from Bangladesh’s Disaster Management Systems

The cyclone-battered nation of Bangladesh is a world leader in disaster preparedness and resilience building. In 1970, Cyclone Bhola killed 500,000 people in the country, making it the deadliest cyclone in world history. Today, Bangladesh is recognised as a “role model” in cyclone management, with a system focused on forecasting, warning, evacuation and local action – which has saved thousands of lives since.

Researchers from the UCL Institute for Risk and Disaster Reduction analysed some key features of Bangladesh’s success. In 1970, the country had just 42 cyclone shelters – this number now exceeds 12,000. It has also established a diverse system of warning and evacuation messages tailored to local needs, ranging from social media to people on bicycles with megaphones and emergency services. Local groups also collaborate to implement schemes such as mangrove enhancement to protect from storm surges and rainfall.

One local program, named “Vulnerability to Resilience”, engaged the community to participate in its own resilience-building work. The researchers noted that the outcomes also improved “livelihoods, living conditions, community interaction, health and safety irrespective of a storm”. The program also paid back almost five times the amount invested through enhanced income and local activities, demonstrating the powerful and long-term benefits of engaging local communities in disaster preparedness.

As the globe continues to heat, models similar to Bangladesh’s will be crucial for preventing the worst effects on societies and losses of life from extreme weather events. The post-disaster environments often give communities time to reflect on what went wrong and what can be learnt from the shock, but without stern and quick action, yesterday’s mistakes may repeat themselves.

Evelyn Smail

Writer, United Kingdom

Evelyn is a freelance writer and journalist specialising in climate science and policy, the just energy transition and the human impacts of climate change. She writes for independent publications, NGOs and environmental organisations. Evelyn has a background in sustainable development, climate justice and human rights.

Evelyn is a freelance writer and journalist specialising in climate science and policy, the just energy transition and the human impacts of climate change. She writes for independent publications, NGOs and environmental organisations. Evelyn has a background in sustainable development, climate justice and human rights.