Recently, the New York Times published an article about a special operation by a Brazilian environmental special forces team, arriving deep in the Amazon forest by helicopter, to raze an illegal mining operation on Indigenous land. The article brought to mind the contrast between that operation and what I have documented in the remaining rainforests of Southeast Asia.

In Malaysia – where I have done much of my work – far from government law enforcement coming to the defence of Indigenous land rights, Indigenous peoples and activists have, again, for decades, been arrested by private company security or police for erecting barricades to keep resource extraction companies from cutting down their ancestral forests, contaminating their rivers with mining effluent or from grabbing their lands outright.

Oil Palm Plantations and the Effects on the Batek Indigenous People

In 2010, the massive BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill was generating a lot of talk about how “green”, renewable biofuel could be an alternative to petroleum. Palm oil, in addition to being used for various food and personal hygiene products, was also being touted as a source of biofuel.

In Malaysia, perhaps no Indigenous people have lost more of their ancestral homeland to oil palm-land conversion than the Indigenous Batek people.

The Batek, part of the first waves of humans to emerge from the African continent, eventually traced, by foot, the Indian Ocean coastline before arriving in Southeast Asia 80,000 to 100,000 years ago. They lived sustainably in Peninsular Malaysia’s 110-million-year-old forests, the largest living carbon sink.

I knew that Taman Negara National Park – a 4,343 square-km area of protected, old-growth rainforest and the most diverse ecosystem on the planet, which harbours tigers, Asian elephants, Malaysian gaurs (wild bovine), tapirs, gibbons, monkeys, over 300 species of birds, over 1,000 species of butterflies and over 14,500 species of flowering plants and trees – lay at the heart of their traditional territory.

Deforestation in Malaysia and the Batek

During that first reporting trip in 2010, park officials in Kuala Koh deflected all questions I had about the Batek. So, I decided to take the short walk to the edge of the national park to the Batek’s government settlement.

I saw a family. At first glance, the family, sheltered from the sun by a palm thatch roof on a bamboo porch, looked more like they could have stepped out from the Congo Basin rainforest than this one in Southeast Asia. In a country where people generally have straight black hair, the Batek have woolly hair and a darker complexion, and adults are rarely taller than 150 cm.

Although I did not know it then, I was about to meet the extended family of Mahmet Pokok, who would become headman during unprecedentedly turbulent times. The days when the hunter-gathering Batek lived far from any road were already long gone, with the deforestation in Malaysia contributing to this.

The paved access road into the national park headquarters in Kuala Koh passed through 30 km of nonstop oil palm plantations – all of it the Batek’s former hunting grounds. The presence of a road also opened up easy access to the national park for poachers, often from Thailand and even Vietnam, who often come to hunt endangered species for traditional medicine and the pet trade. The Batek say they give an increasing number of poachers a wide berth in the forest for safety reasons.

Meanwhile, loggers have cleared away most of the former buffer forest and oil palm plantations that abut much of the national park’s boundary.

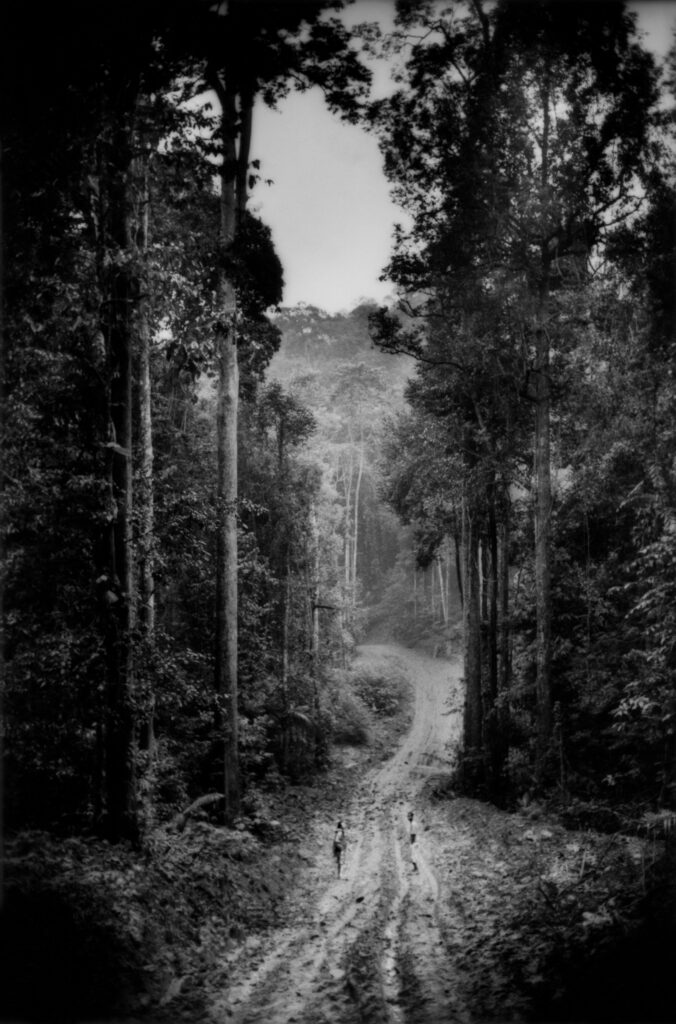

Mahmet Pokok pointed me to a dirt road heading into a mature secondary forest. It was a buffer forest adjacent to the national park, where this clan had a cooler settlement by a river. They had lost a lot, but it was still possible to maintain a somewhat semi-nomadic lifestyle. However, change was afoot.

The following year, the road to the forest settlement had been widened, and bulldozers had encroached far deeper into the forest. More ominously, however, survey markers had been planted on stakes at muddy intersections. The Batek assured me that there would be selective logging and nothing else as we walked past a logging camp.

By the time I returned in 2015, deforestation in Malaysia was on the rise, and the buffer forest had been cut without the Batek’s consent and despite loggers’ previous promises. With the thin topsoil now washed away, the inorganic orange undersoil was terraced and planted with waist-high oil palms, which were nourished by chemical fertilisers that washed into the same river where the Batek drank and bathed.

The logging company did, however, make one concession. While the perimeter of the plantation was strung with electrical wire to keep out the forest elephants, the authorities agreed not to electrify the fence near where the Batek and their children lived. In the end, so few trees remained at the riverside settlement the Batek abandoned it due to excessive heat and little shade. The alternative saw them move to the government settlement, which was, by then, a collection of seven or eight furnace-hot, tin-roofed concrete structures.

Manganese Mining and the Poisoning of the Tonduk River

Just when it seemed things could not get any worse, in 2016, a manganese mine broke ground directly above the main water source for the government settlement, the Tonduk River. The clan could no longer draw drinking water or fish from the river.

A couple years later, in May 2019, high fevers set in for the Batek communities downriver. “Their throats swelled and then they couldn’t swallow or eat,” headman Mahmet Pokok recalled. In rapid succession, one after another, the Batek of Kuala Koh began to fall ill.

“Soon, people couldn’t breathe,” Pokok continued. “They shrivelled and their bodies turned black,” he said. Then, some began to die.

The measles epidemic spread like wildfire through cramped concrete houses, a situation exacerbated by malnutrition and contaminated water. It claimed 16 lives within two weeks in a community of 186. In the end, 100 Batek would be hospitalised, and only 20 were left unaffected.

Traditionally, when illness struck, the nomadic Batek used the epidemiologically sound practice of abandoning a settlement and setting up someplace safer. This was no longer an option for them, as their nomadic origins were but a thing of the past.

The Batek Losing Ground to Deforestation in Malaysia

It was hard to imagine, in 2010, the apocalyptic decade that lay ahead for this clan of Indigenous people who seemed to have lost so much already. After decades of intensifying encroachment on their ancestral land, the people’s collective knowledge about living sustainably in the environment, especially as the climate crisis delivers wild fluctuations in global weather patterns, could be lost forever. Now, for the first time in their history, the Batek of Kuala Koh are completely surrounded by palm oil plantations – one of the main drivers of deforestation in Malaysia.

History is littered with extinct peoples, along with their collective wisdom. Across the Indian Ocean, in 2010, the last living member of the Bo, another so-called Negrito people, died in the Andaman Islands of India. The Bo, their language and their customs are now gone. So, while there are still Batek in Malaysia, there is hope. But the better question is, what can they teach us about environmental sustainability? And better yet, at what cost is the globe willing to accept to fuel an ever-expanding palette of products containing palm oil at the expense of Indigenous people’s lives?

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Climate Impacts Tracker Asia.

James Whitlow Delano

Documentary storyteller, Japan

James is a documentary storyteller and photographer who has been based in Asia for over 20 years but whose work spans across the globe. James' career has focused on environmental issues and climate change, human rights, migration and Indigenous cultures affected by industrialisation. His projects have won awards, such as the Alfred Eisenstadt Award (from Columbia University and Life Magazine), Leica's Oskar Barnack, Picture of the Year International and NPPA Best of Photojournalism. He is also a grantee from the Pulitzer Center. James' work has been covered by publications like The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, New Republic, The Guardian, Foreign Policy and many more. He is the founder of the EverydayClimateChange Instagram feed.

James is a documentary storyteller and photographer who has been based in Asia for over 20 years but whose work spans across the globe. James' career has focused on environmental issues and climate change, human rights, migration and Indigenous cultures affected by industrialisation. His projects have won awards, such as the Alfred Eisenstadt Award (from Columbia University and Life Magazine), Leica's Oskar Barnack, Picture of the Year International and NPPA Best of Photojournalism. He is also a grantee from the Pulitzer Center. James' work has been covered by publications like The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, New Republic, The Guardian, Foreign Policy and many more. He is the founder of the EverydayClimateChange Instagram feed.