Air pollution, caused by fossil fuel emissions, damages human health and the healthcare systems that people depend on in times of crisis. Apart from respiratory disease and cardiovascular issues, widespread air pollution can also contribute to lung cancer, neurological and reproductive issues and a compromised immune system – issues that can seriously impact human lives.

Health Impacts of Extreme Weather

Scientists now warn fossil fuels and extreme weather are also threatening our hospitals, the very sanctuaries of healing that should be providing the care such serious diseases require.

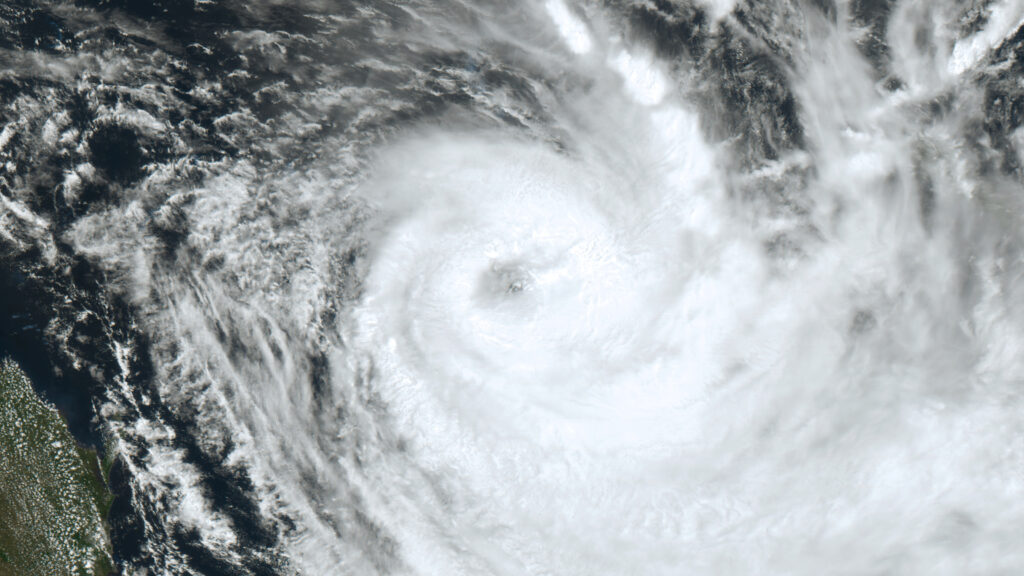

Impacts from extreme weather, fueled by unchecked fossil fuel emissions, threaten one in every twelve hospitals globally with a total or partial shutdown by 2100, according to a new report by XDI, a global leader in physical climate risk. Southeast Asia will be the most affected region, with one in five hospitals at risk.

XDI: Asia Faces the Highest Risk of Hospital Closure Due to Climate Change and Extreme Weather Impacts

According to the 2023 XDI Global Hospital Infrastructure Physical Climate Risk Report, without a rapid fossil fuel phaseout, 16,245 hospitals globally will be at risk of partial or total closure by the decade’s end due to extreme weather impacts like hurricanes, flooding, severe storms and forest fires. For reference, the authors note that a residential or commercial building with this level of risk would be considered uninsurable.

However, the risk of climate change to hospitals isn’t spread proportionally. Communities in low and middle-income countries are most likely to suffer from the lack of emergency hospital care, with 71% of hospitals in these countries at risk.

Southeast Asia tops the chart of the most affected regions in a high emissions scenario. The region is home to 18.4% of the high-risk hospitals. Without a rapid emissions reduction, the overall risk of damage to regional hospitals will more than quadruple by 2100 – a 348% increase.

The authors warn that, by 2050, a third of the hospitals with the highest risk will be in South Asia.

By 2100, the main threats to hospital infrastructure across Asia will be riverine flooding, surface water flooding and coastal inundation.

Indonesia

The study identifies Indonesia as having the highest number of high-risk hospitals in Southeast Asia. By 2050, 509 health facilities will be at risk of partial or total shutdown. By the end of the century, the number is expected to reach 696. As a result, Indonesia will rank in the top five countries with the most hospitals at risk of damage due to extreme weather impacts worldwide.

Vietnam, the Philippines and Laos

Without a rapid emission reduction, one in every four hospitals in these nations will be particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events by 2100.

Laos will experience the greatest increase in the percentage of high-risk hospitals in the region, with 32.4%. It will also see the highest jump in damage risk across all hospitals – an increase of more than 500%.

Since 1990, the risk of damage to Vietnam’s hospital infrastructure has almost tripled due to climate change, with a 178% increase.

While coastal inundation and flooding will be the dominant hazards in most of Southeast Asia, countries like Malaysia, Singapore, Laos and Cambodia are also likely to experience an increase in extreme wind by 2050.

Singapore

While hospitals across Singapore are constructed according to higher standards than the rest of the region, they won’t be left unscathed.

Singapore is likely to experience the second-greatest increase in damage risk by 2100 in the region, with 467%. However, if emissions are rapidly phased out, the risk increase drops to 124%.

India

India is the main reason South Asia has the highest number of high-risk hospitals globally. According to the XDI study, 2,700 of India’s over 53,000 hospitals are already at increased risk of partial or complete shutdown due to the impact of extreme weather. Without a rapid fossil fuel phaseout, the number will jump to more than 5,100, or over one in 10, by 2100. As a result, India will have the most hospitals at risk, far ahead of China (1,302).

Bangladesh

One in seven hospitals in the country will be at high risk of being shut down by extreme weather impacts by 2100 if emissions remain high. If this occurs, Bangladesh would rank 14th on the list of countries with the most hospitals at risk.

China

In a 1.8°C global warming scenario, China’s hospitals will have the highest risk rating in East Asia, with 1,302 hospitals affected by 2100. Globally, it would be second only to India.

Furthermore, in a case of no rapid emission reduction, China will have the highest percentage of high-risk hospitals – 15.1% by 2100. Overall, the damage risk across China’s hospital infrastructure will jump 462% by the end of the century. On the other hand, a low emissions scenario will see this damage risk drop to 187%.

Japan and South Korea

More than one in 10 hospitals in Japan will be at risk of complete or partial shutdown by 2100. By the end of the century, it will likely experience a 500% increase in the risk of damage to its hospital infrastructure. The result will be the highest in East Asia. Japan will have the third-highest number of hospitals at risk by 2100, only behind India and China. However, this number could drop to 219% if emissions are reduced rapidly.

In South Korea, 7.5% of the hospitals will be at risk of being shut down by extreme weather by 2100. As a result, it would have the fourth-most hospitals at risk.

United Arab Emirates

Since 1990, the country has experienced a 239% increase in damage risk and ranks among the top 10 countries most impacted. The UAE will feel the most significant impact in West Asia from weather events like coastal inundation and flooding.

By 2050, 12.6% of hospitals in the UAE will be at high risk of being shut down due to extreme weather events. Without a rapid emission reduction, the figure will jump to nearly one in five by 2100.

However, the authors of the study note that unlike many of its Asian peers, the UAE has been building its hospitals according to codes that are likely to help them withstand severe storms, rising sea levels and flooding. Furthermore, the country has the resources to fund adaptation for hospitals that require it.

Fossil Fuels Are Increasing Stress on the Healthcare System

Southeast Asia is already experiencing the greatest increase in the risk of damage from climate change and extreme weather impacts: 67% since 1990. In South Asia, the increase is 40%, while in the eastern part of the continent, it is 35%.

Aside from being the regions with the highest number and proportion of high-risk hospitals, XDI identifies Southeast Asia, East Asia and South Asia as the regions where many countries’ health systems are already struggling. The authors warn of the risk of a complete breakdown in healthcare delivery in places where hospitals fail.

“The impact of climate change on health systems has been hidden in plain sight,” says Eloise Todd, executive director and co-founder of the Pandemic Action Network.

Aside from the material risk to physical assets and infrastructure, the strain of fossil fuels on the health system is also projected to increase due to their harmful health impacts.

“It is clear that climate change threatens to undermine the stability of the health systems our patients and communities depend on,” notes Professor Nick Watts, director of the Centre for Sustainable Medicine at the National University of Singapore. “Whether it results in the closing of health facilities or a clinic becoming overwhelmed with rising burdens of disease, the human consequences are dire,” he says.

Air, Water and Land Pollution

Fossil fuels turn the air into a toxic cocktail of PM 2.5 and other deadly pollutants.

For example, burning coal releases various heavy metals, particulates and gases, including mercury, lead, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and more. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, health impacts from these emissions can range from asthma and breathing difficulties to brain damage, heart problems, cancer, neurological disorders and premature death. Furthermore, recent research finds that air pollution from coal stations is much more deadly than initially thought. Exposure to PM 2.5 from coal-fired power plants has over double the mortality risk than pollution from other sources.

Although often dubbed a cleaner alternative than coal, natural gas’ exploration, drilling and production practices emit a range of pollutants, particularly matter and heavy metals, negatively impacting water, soil and wildlife. While gas is generally perceived to lead to considerably fewer casualties than coal and oil, a Harvard research team has found that deaths related to gas emissions can exceed those of coal.

Meanwhile, research from the University of Chicago finds that South Asia is the region with the most polluted air. Additionally, over 70% of all deaths related to air pollution occur in the Asia-Pacific region.

According to estimates, without the air pollution caused by fossil fuels, the average life expectancy in South Asia would increase by over five years. For some regions like New Delhi in India, air pollution slashes the average lifespan by over a decade.

The costs accompanying fossil fuel air pollution in China and India are USD 900 billion and USD 150 billion annually, respectively.

Increased Risk of Pandemics

Scientists from Georgetown University suggest that climate change could be the biggest upstream risk factor for disease emergence, especially for animal-to-human virus transmission.

“We know that increased temperatures mean more pandemic threats,” explains Eloise Todd. “Climate change will put entire health systems at risk of climate breakdown just as they will be put under more pressure,” she adds.

Scientists expect at least 15,000 instances of zoonotic spillovers, or viruses jumping between species, in the next 50 years. The reason is that many animals will have to move into new areas due to climate change. They will bring their parasites and pathogens with them in the process, causing a potential spread between species that haven’t interacted before. Currently, at least 10,000 types of viruses capable of infecting humans circulate in wild animal populations. Due to the increased habitat destruction, crossover infections might become more probable, especially in high-elevation areas in Africa and Asia.

A study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that the likelihood of an extreme epidemic, or one similar to COVID-19, will increase threefold in the coming decades.

Scientists from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa find that climate change has already exacerbated over 200 infectious diseases. Furthermore, extreme weather impacts have aggravated 58% of the contagious diseases confronted by humanity globally at some point, including pushing up the number of cases, making conditions more severe and hampering people’s ability to cope.

“The human impact of 1 in 12 hospitals shutting down – and up to 1 in 5 in South East Asia – would be nothing less than catastrophic,” said Todd. “It’s time to stop the burning of fossil fuels and invest in climate- and pandemic-resilient health systems – the two can and must go hand in hand,” she added.

Public Pressure Key To Ending Fossil Fuels and Preserving Our Health and Health System

According to the authors of the XDI study, South Asia has the most to gain from a lower emissions trajectory. Limiting the temperature increase to 1.8°C will reduce the increase in risk to hospital infrastructure to 76% by the end of the century, compared to 295% in a high emissions scenario.

Director of Science and Technology at XDI, Dr. Karl Mallon, states, “The most obvious thing to dramatically reduce this risk to hospitals and keep communities safe is to reduce emissions.”

Phasing Fossil Fuels Out

Global momentum for ending coal use started at COP26, with leading emitters pledging to phase out its use in the 2030s. Smaller economies agreed to follow suit in the 2040s. However, not all are on the same page. The 2023 Global Coal Exit List reveals that companies and leading financiers still plan to develop 516 GW of new coal-fired capacity. If completed, these projects would increase the world’s current installed coal-fired capacity by 25%.

Countries like Japan, for example, are trying to extend the life of existing coal infrastructure through technologies like ammonia-coal co-firing and CCS. Furthermore, it plans to export these technologies to Southeast Asia.

The southern and eastern parts of Asia are among the most vulnerable to climate change. However, Asian corporations and governments have voluntarily thrown fuel into the fire by planning a significant global coal and gas expansion.

NGOs, affected communities and societal and religious groups across Asia are already opposing fossil fuel expansion plans, with some efforts managing to delay or cancel particular projects.

Southeast Asia, for example, has seen an 86% drop in new coal projects since 2015. According to E3G, 2.4 GW of coal power has been cancelled for every 1 GW that has entered into operation for the past seven years.

While the lack of economic reasoning and the looming climate crisis are major reasons for this, public pressure from affected communities has also played a major role.

For example, over 140 groups from 18 countries wrote Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida a letter asking to stop the expansion of fossil fuels and the derailment of Asia’s clean energy transition. Activist movements have already managed to stop some of Japan’s projects in Bangladesh and Indonesia.

After this year’s G7 meeting, international religious organisations that united over 600 million people from more than 190 countries wrote an open letter of complaint. They expressed “grave disappointment” at the fact that G7 leaders considered public investments in fossil fuels “appropriate,” called for gas sector expansion and failed to commit to a coal phaseout date of 2030.

In the Philippines, joint efforts from frontline communities, fishermen, religious groups and civil society organisations against fossil fuel expansion in the country have also been successful. Activists even managed to delay or cancel some of the San Miguel Corporation’s gas projects in the country. Local organisations also launched a campaign against banks and investment firms supporting the fossil fuel projects in the Verde Island Passage. Furthermore, organisations plan to attend annual general meetings of banks across the Philippines, Japan and Europe to oppose fossil fuel project financing.

Need For Adaptation and Mitigation Financing

Cutting emissions alone won’t eradicate the physical risk to the hospital system entirely. As a result, the XDI study’s authors note that all affected facilities require adaptation. However, they also acknowledge that this will require enormous investment. For many, the only choice might be relocation. This would be a glaring problem for developing Asian countries, which are among the most vulnerable to climate change and face the most challenges to a fair and just transition.

Having the wealthiest countries finally deliver the promised USD 100 billion in annual climate support and increasing the aid to adequate levels will significantly help build developing nations’ adaptation and mitigation ability.

Towards COP28

Fossil fuels have been powering the global economy for over 150 years. While coal reserves, in particular, will likely last for another 150 years, the world cannot afford to wait. In 2023, the world saw the highest global temperatures in over 100,000 years. According to the UN, the world is on track for a temperature increase of 2.9°C, with a 14% chance of limiting it to 1.5°C. To prevent the worst impacts of the looming catastrophe, UN chief António Guterres urged “tearing out the poisoned root of the climate crisis: fossil fuels.”

In a recent report, the IEA also urged the fossil fuel industry to use COP28 as a stage to take action.

The UAE, the COP28 hosting nation, and other leading fossil fuel producers have already called for a more realistic energy transition in which fossil fuels would still play a part.

However, with 1,337 tonnes of CO2 emitted every second, the world is running out of time.

The XDI study shows that with extreme weather impacts posing a real threat to the hospital system, people’s health is at the mercy of a select few and their decisions about fossil fuels. To raise awareness about the severity of the problem and urge governments and communities to act, XDI is releasing the names, locations and levels of risk for over 200,000 hospitals worldwide.

“Governments have a duty to populations to ensure the ongoing delivery of critical services,” says Dr. Mallon. “For individual governments not to take action on this information, or for the global community not to support governments in need, is a blatant disregard for the wellbeing of their citizens.”

The nearer we get to the climate crisis, the fewer choices we have. But we still have some, and global leaders should start taking them. COP28 will be the perfect stage to see if they are willing to.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.