South Asia is drenched with heavy rains. Homes and cars swept away like toys, livelihoods vanishing under relentless muddy rivers and personal belongings lost – July’s extreme rainfall brought flash floods and landslides, turning peaceful villages into scenes of destruction in just a couple of hours. The aftermath: a trail of devastation that will haunt those who survived long after the waters have receded, as they seek to rebuild their lives from the mud and debris.

“The water rose so fast that we barely managed to escape,” says Manoj, an owner of a small shop, as he recalls the flash flood hitting his village in Assam, India, in June. “Everything is destroyed, and I have to start from scratch.”

In many ways, Manoj was lucky. Hundreds of others couldn’t escape the floods and lost their lives.

The scale of the recent disaster is a grim reminder of South Asia’s vulnerability to extreme weather. Worryingly, scientists warn that the floods tormenting the region this summer are only likely to intensify. Alternatively, without urgent emissions reduction efforts and the scaling up of investments in adaptation, today’s events could be tomorrow’s best-case scenario.

Another Summer, More Extreme Rainfall and Floods Tormenting South Asia

The period between May and July 2024 brought South Asia torrential rain, triggering large-scale flash floods and landslides.

In India, floods claimed the lives of at least 250 people just weeks after the end of the country’s longest-ever heatwave. The heavy rain affected over 1 million people and 1,500 villages in Uttar Pradesh, the largest state. In the Assam province, the floods following the record-high rainfall between June and July affected over 2.4 million people and inundated over 1,300 villages. After an extreme monsoon downpour on July 30, Wayanad in northern Kerala, was hit by massive landslides that killed hundreds of people, while floods washed away bridges, destroyed homes and roads and caused power outages. According to scientists from WWA, climate change has increased the likelihood and intensity of the rainfall, which triggered the disaster. An event like this was projected to occur once every 50 years.

In Bangladesh, relentless floods affected over 2 million people, among which 772,000 children.

Record rainfall, flash floods and landslides have taken the lives of over 170 people and displaced tens of thousands in Nepal since May.

In Pakistan, heavy monsoon rains lashed several provinces between July and August, causing flash floods, landslides and widespread damage. The death toll reached 178. This brought a painful reminder of the 2022 catastrophic flood that inundated a third of the country, killing 1,700 people and displacing 33 million.

Indonesia was also battered by heavy torrential rains, which flooded different parts of Java and triggered a deadly landslide in Sulawesi. The disaster damaged houses and bridge infrastructure and killed 12 people, with another 18 missing. In March, flash floods and landslides on Sumatra island killed at least 30 people.

Thailand was also severely affected, with flooding in the southern parts damaging hospitals and destroying homes.

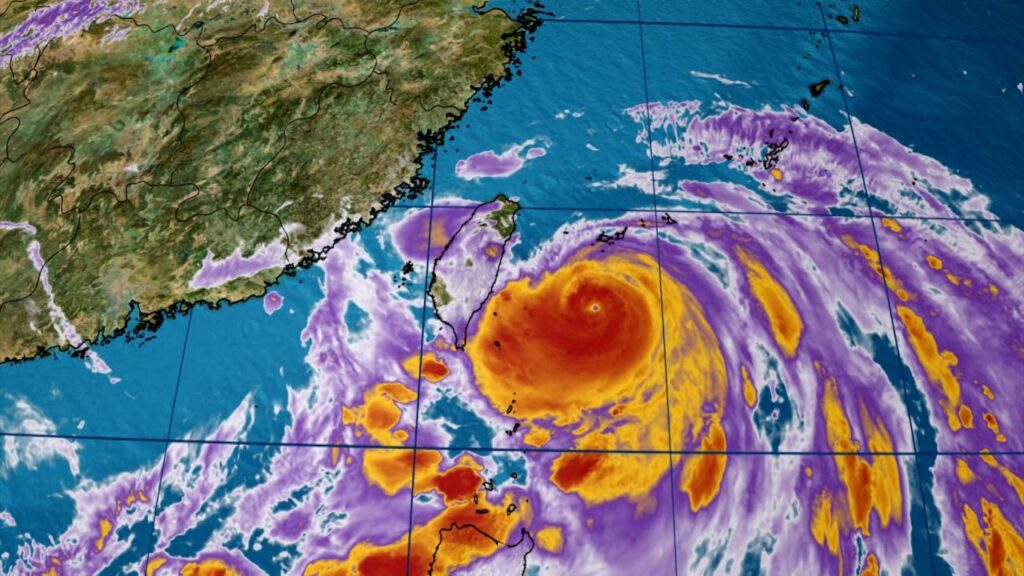

At the end of July, Typhoon Prapiroon, the second typhoon to hit the East Sea this year, brought up to 300 mm in rainfall and wind speeds of over 100 km. Around 6,000 visitors were left stranded on the Cat Ba and Co To islands in northern Vietnam. Cruise ships with thousands of passengers had to suspend operations and visits to Vietnam’s Ha Long and Lan Ha Bay.

The Triggers For the Extreme Rainfall

Scientists say flooding from annual monsoon rains is common in South Asia, but climate change further exacerbates its impact.

A common denominator for the disasters taking place over the past two years is the role of flash floods, triggered by heavy rain in a short period of time in particular hotspots. As a result, major rivers can quickly breach embankments and inundate coastal areas. For example, the increased precipitation over Bangladesh in July raised the Brahmaputra River’s level by 2-2.5 m in just three days. Paired with the accelerated rate of urbanisation and the lack of adequate infrastructure to accommodate it, South Asian countries are shaping up as a hotspot for water-related disasters.

According to Unicef, the torrential rain, deadly flash floods and landslides that have been tormenting South Asia in the past months have put over 6 million children at risk. The situation is likely to worsen considering that, according to the WMO, the monsoon season, which brings around 90% of South Asia’s annual rainfall and recurring floods, is expected to last until September.

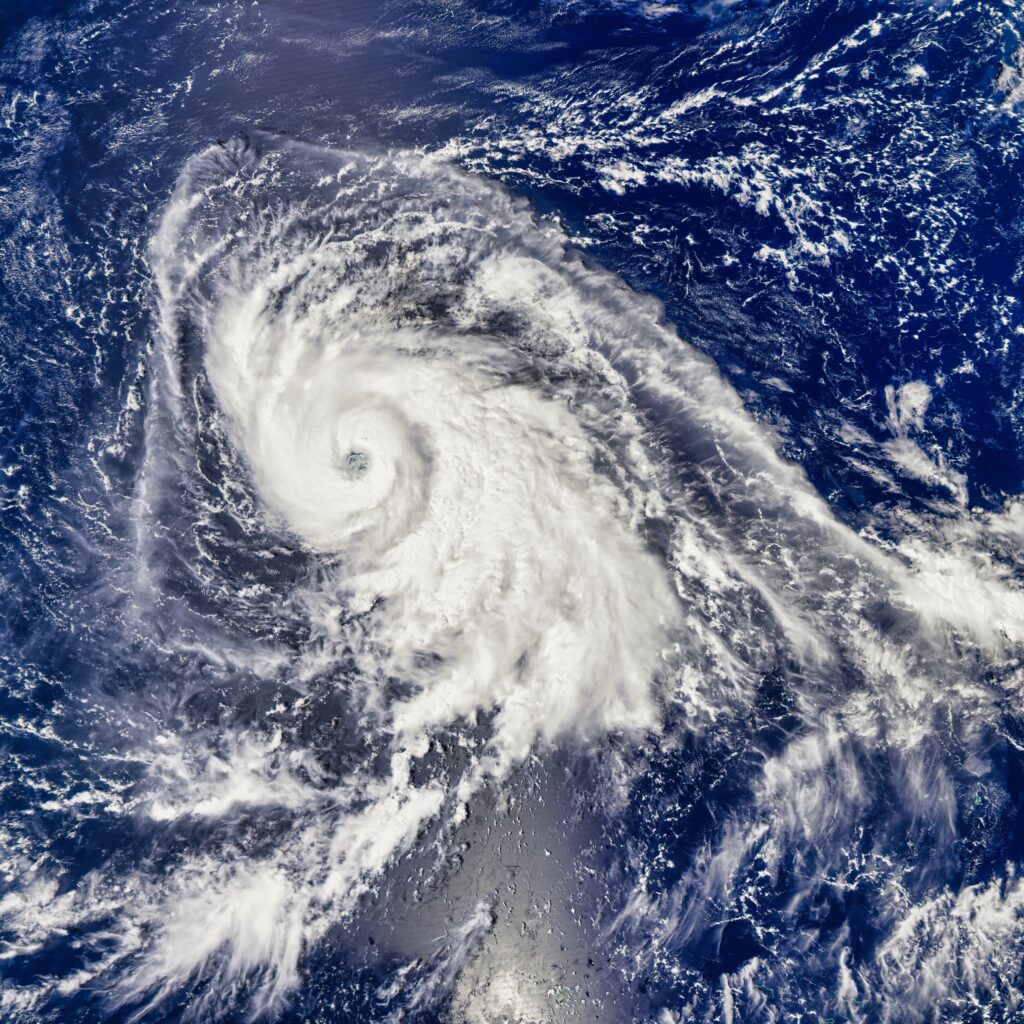

Meteorologists also identify the transition from El Niño to La Niña as another reason for the wetter weather conditions to extend into the second half of the year. The process typically brings higher precipitation to Southeast Asia and India. Some countries, like the Philippines, are already bracing for more storms than in the past year when 11 tropical typhoons hit the country. According to the World Bank, storm flooding has caused 30,000 deaths in the country over the past 30 years.

Gloomy Projections Await South Asia

“Floods have gotten more frequent and worse over time. I am afraid of what will follow next,” says Manoj. His observations align with scientific evidence.

According to the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), Asia is the world’s most disaster-hit region by weather, climate and water-related hazards. In 2023, floods and storms caused the most reported casualties and economic losses. Over the past year, Asia was hit by 79 hydro-meteorological disasters. Over 80% were related to flood and storm events, causing more than 2,000 fatalities and directly affecting 9 million people.

According to data from the International Disaster Database, Central and Southeast Asian countries, including India, Pakistan, China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines, have seen the most floods from 2000-2022. The region had among the highest numbers of people impacted per square km. In India, extreme rainfall events have tripled since 1950.

The main reason is that Asia is warming faster than the global average, with the rate nearly doubling since the 1961–1990 period. Climate scientists reveal that a similar worrying trend will continue charting Asia’s future. According to an analysis of 146 climate models, Asia will become significantly exposed to extreme rainfalls and flood risk by 2030. No other continent will face such substantial rainfall changes.

According to the study, of the 25 countries likely to experience increased wetting patterns, 12 are in Asia. Over 70% of the examined models show that highly populated areas, home to over 2.7 billion people in China and India, will experience increased rainfall. Other significantly affected Asian countries include Bangladesh, Japan, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia.

The risk of riverine flooding due to extreme rainfall and flash floods is also high in most parts of Asia. Southeast Asia, along with countries like Bangladesh and Pakistan, will be the most affected.

Similar is the case with sea level rise, since 17 of the 20 fastest-sinking cities between 2015 and 2020 were in Asia.

In Singapore, for example, the sea level could rise by 1 m by 2100, according to the national water agency.

Vietnam faces the highest risk of coastal flooding in Southeast Asia. Both Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi, which are located near highly flood-prone deltas, are especially vulnerable.

When it comes to the Philippines, Metro Manila currently sinks by 10 cm annually.

By 2030, 96% of Thailand’s capital, Bangkok, could be flooded, while 80% of Mumbai could end up underwater by 2050.

Asia’s Adaptation Efforts Show Promise, But More Action Needed

According to the World Bank, 70% of the most flood-exposed people live in South and East Asia. Studies reveal that the number of people living in highly flood-prone areas in East Asia has outpaced settlements in flood-safe zones by 60% in the three decades to 2015, with the biggest growth in China (233%). In addition, due to the accelerated rate of urbanisation, many of the water bodies, floodplains, natural stormwater channels and green spaces in big cities in India and across Southeast Asia have been lost, increasing the risk of urban flooding. Alongside the growing severity of the climate crisis, these factors highlight the importance of governments being perpetually prepared to respond to extreme weather events.

Fortunately, there are bright examples, with most Asian countries actively investing in new infrastructure capable of withstanding long-term risks. They are also working on making existing infrastructure more resilient.

China

China is among the most vulnerable countries to floods, with nearly 400 million people, or a third of the global total, being at risk of once-in-100-year floods.

To protect them, in 2015, the government started building so-called sponge cities, nature-based, water-resilient cities designed to withstand regional floods by making space for water. The idea behind the project is to develop storage ponds and wetlands and create permeable road infrastructure to soak stormwater into the ground. The design also focuses on building big parks in and around cities with dedicated water storage tunnels, rain gardens and wetlands. They serve two primary purposes: to act as an additional drainage system and prevent flooding, and ensure water reserves in periods of extreme drought.

Among the best sponge-city examples is Shenzhen. After investing over USD 320 billion between 2016 and 2022, experts consider it protected against heavy floods occurring once every 100 to 200 years. However, last year, the flood that hit the city was a “one-in-500-year disaster.”

China aims to turn 80% of urban areas into sponge cities by 2030, recycling 70% of rainfall. However, experts are clear that the success of the concept depends on quick mass implementation. Furthermore, they note that due to the uncertainty around climate change, relying on sponge cities alone isn’t a viable strategy unless backed with other adaptation solutions and mitigation efforts.

The country has also introduced a very advanced, interconnected, standardised, and unified early-warning system. It relies on rapid and effective response and multi-sectoral application to issue precise early disaster warnings to people in cities, villages and rural areas in affected regions.

South and Southeast Asia

Singapore is among the global success stories when it comes to the adoption of aquifers. The country successfully mitigates floods by building underground reservoirs and monitoring data for their performance. In addition, the aquifers help address the nation’s water scarcity problem. The country even recently launched a first-of-its-kind nature-based aquifer to help mitigate the impact of floods.

In Malaysia, where the number of floods is likely to increase by at least 20% in the next five years, the government has prioritised the adoption of early-warning systems and is building multi-tiered smart tunnels, tube wells and underground reservoirs to protect against coastal flooding and flash floods. In the 12th Malaysia Plan, it has committed to allocating almost USD 4.8 billion (RM22 billion) for flood mitigation projects. The country is also partnering with the Netherlands to leverage its renowned expertise in flood management by integrating water bodies and advanced drainage systems into cities and rural towns.

The Philippines invests heavily in building dams and flood control projects, allocating up to 9.4% of its total budget to climate-related initiatives.

Vietnam is another country that has prioritised the buildup of retention ponds and underground rainwater storage tanks to protect against floods. Furthermore, the government actively monitors water consumption and has prioritised the creation of digital maps for drought warnings and improving wastewater treatment.

Scientists from Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar are collaborating with NASA to build tools that use satellite data to predict extreme rainfall better and track the water levels across the Mekong River.

Through different initiatives, the WMO actively supports Cambodia and Laos in strengthening effective and risk-informed early warning services against floods in line with the UN’s Early Warnings For All program.

According to Armida Salsiah Alisjahbana, executive secretary of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, early warning and better preparedness saved thousands of lives when tropical Cyclone Mocha hit Bangladesh and Myanmar in 2023.

Other innovative applications of technology for disaster management and vulnerability analysis include Project Sunny Lives in India, led by Microsoft, which has formed an inundation risk assessment system for highly vulnerable areas. By using IoT sensors and drone imagery, the International Water Management Institute monitors water levels, conducts hazard and risk mapping and helps locate survivors after disasters in pilot projects in South Asia.

However, technology should be accompanied by nature-based solutions such as wetland restoration, water retention area development, reviving old channels, sustainable land use, afforestation and reforestation and more. This combination can ensure more efficient flood risk management and protection against landslides, erosion and other water-related hazards.

Adaptation Alone Falls Short, Mitigation Also a Critical Priority

Scaling up financing and mass adoption of climate change adaptation strategies is just one aspect of Asia’s battle against the looming threat of extreme rainfall, floods and sea level rise. Equally important is the focus on mitigation since climate scientists say that the only way to avoid the worst scenarios in their studies is immediate and deep CO2 emission reduction.

While China is already leading the world on that front, the rest of Asia is stalling. Since the continent is responsible for 50% of the global emissions, it needs to scrap quick-fix energy system solutions and prioritise long-term, sustainable action as quickly as possible. Otherwise, millions will find themselves in Manoj’s shoes.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.