“In this disposable age, is there a reason for the non-disposable bottle?” an ad for disposable baby bottles said back in 1971. Advertising from this era urged people to throw things away by emphasising that plastic packaging and cans were so cheap that it was better to dispose of them when no longer needed.

Fast forward 50 years and today, people worldwide buy around a million plastic beverage bottles per minute.

Plastic Waste

Plastic waste and microplastics are everywhere — from plastic bags at the bottom of the deepest ocean trench to microplastics in the clouds, on Mount Everest, in the Antarctic snow and even in our brains. In fact, they are so embedded into our existence and nature that scientists believe they could serve as a geological indicator of the Anthropocene era.

Disturbingly, despite recycling initiatives and novel technologies to substitute single-use and virgin plastic, the OECD estimates that annual plastics production, use and waste generation will increase by 70% in 2040 compared to 2020 if we don’t act today. According to the WWF, 85% of people support a ban on single-use plastics, 90% support a ban on hazardous chemicals used in plastics and 87% support reducing global plastic production. Still, similar to the climate crisis, a handful of petrostates hold the world hostage, blocking any efforts to accelerate the move away from plastics.

The Proportions of Global Plastic Pollution and Production Problems

The first form of plastic was invented in 1862. Still, the problems the world has on its hands today didn’t start until the post-war period when it went mainstream, replacing the more expensive paper, glass and metal materials used in throwaway items.

Today, the production of consumer packaging, such as PET bottles (500 billion sold per year) and plastic bags (5 trillion produced per year), as well as their irresponsible handling, are some of the biggest sources of plastic pollution.

To date, we have produced over 8 billion tonnes of plastic, with just 9% recycled. According to the UNEP, we generate about 400 million tonnes of plastic waste annually, with around half of the manufactured plastic being single-use.

In the film “The Story of Stuff,” Annie Leonard, former executive director of Greenpeace USA, notes: “There is no such thing as ‘away.’ When we throw anything away, it must go somewhere.”

So, where does the used plastic go? The short answer is: everywhere — from the soil and oceans to the atmosphere and the living organisms.

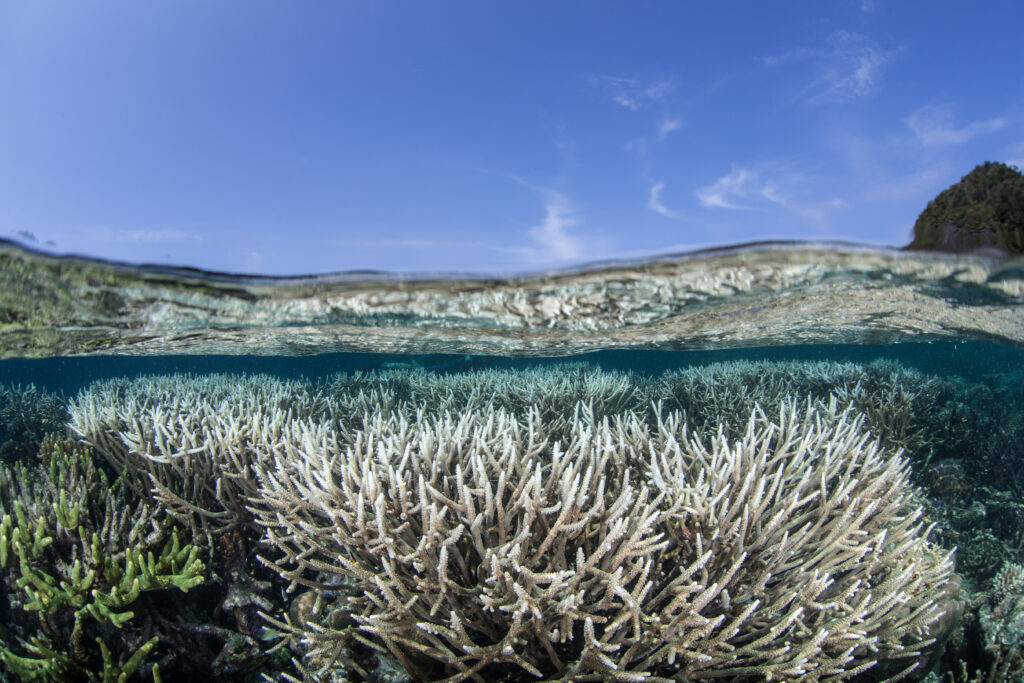

Discarded Plastic – A Threat to the Marine Environment

According to Ocean Cleanup, a non-profit organisation that has embarked on the ambitious mission to clean up 90% of floating ocean plastic pollution by 2040, over 1 million tonnes enters the ocean annually. The UNEP estimates that 75-199 million tonnes of plastic floats in our oceans, making up over 80% of all marine pollution. Without an urgent shift to more responsible plastics production, use and disposal practices, plastic waste entering aquatic ecosystems could nearly triple from 9-14 million tonnes per year in 2016 to a projected 23-37 million tonnes per year by 2040. Some even claim that by mid-century, there could be more plastic waste in the ocean than fish, by weight.

Furthermore, some plastic waste can take up to 500 years to decompose. Even then, it never entirely disappears — it just gets smaller, turning into “microplastics”.

The Impact of Plastic Pollution and Microplastics on Health and Nature

Over a lifetime, a person ends up consuming around 20 kg in microplastics. According to scientists, by weight, we ingest the equivalent of one plastic credit card per week.

Microplastics enter the human body through inhalation and absorption and then accumulate in organs, including the brain, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, gut and even the placentas of newborn babies. There are serious concerns that microscopic particles, and the chemicals associated with them, pose adverse health implications. However, more scientific evidence is needed to explore their extent. Despite the challenges in linking exposure to microplastics and concrete impacts on health, studies have found that plastics can contain a complex combination of potentially toxic chemicals. Of the more than 10,000 unique chemicals comprising plastics, 2,400 are of potential concern. Furthermore, in laboratory tests, microplastics have damaged human cells, causing allergic reactions and cell death. Early research also reveals that they can help disease spread, alter blood chemistry and affect memory. When burned, plastics can cause neurodevelopmental, reproductive and birth defects and much wider environmental pollution dispersion.

Plastic pollution also has an indirect impact on human health. In countries with poor solid waste management systems, including much of Asia, plastic waste is all over urban and suburban areas and water bodies. According to the UNEP, the garbage spots serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes and pests, increasing the transmission of vector-borne diseases, such as malaria.

Studies on the impact of plastics on wildlife, which have been going on for over 40 years already to help inform research into its potential physiological and toxicological effects in humans, show worrying findings. Currently, plastics kill millions of animals every year — from birds to marine wildlife and land-based species — mainly due to entanglement, starvation or pierced organs. Laboratory tests have also found that plastics can cause liver and cell damage, as well as disruptions to reproductive and endocrine systems in many animals. Scientists estimate that by mid-century, all seabird species on the planet will be eating plastics.

The Lesser-known Link Between Plastics and Climate Change

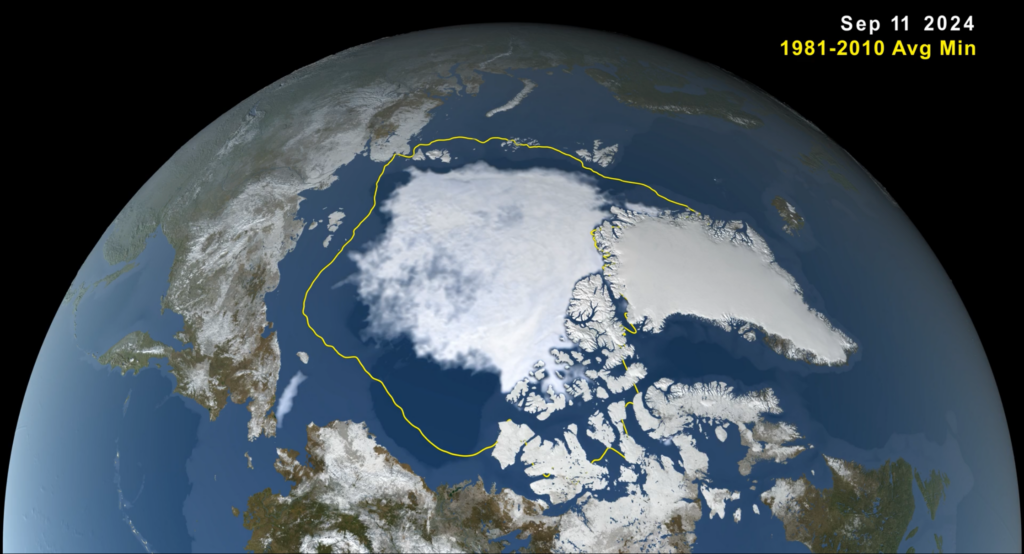

Plastic pollution and climate change are deeply interlinked.

First, 98% of single-use plastic is produced from fossil fuels. In that sense, there is a direct link between the growing demand for plastics and the growing need for more fossil fuels, further slowing down their phaseout.

Plastic production contributes 3.4% of GHG emissions, comparable to the emissions of the entire aviation industry. By 2030, plastic alone could generate more carbon emissions than coal. By 2040, the production, use and disposal of fossil fuel-based plastics will account for 19% of the global carbon budget. According to the Center for International Environmental Law, plastics will be responsible for 20% of all oil consumption by 2050, if the world maintains its current trajectory.

This would significantly negate the impact of reducing fossil fuel use in other sectors, such as transportation, energy and more.

Another plastic-related practice found increasingly harmful to climate and health is open burning, with Asia among the world’s biggest hotspots. Aside from releasing chemicals that harm ecosystems and people breathing the air, the process emits black carbon — a pollutant with a 5,000 times greater global warming potential than CO2. Incineration also emits greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane.

Research reveals that microplastics can disturb the ability of marine organisms, such as plankton, to transform CO2 into oxygen — a crucial process since around half of the oxygen comes from the ocean. Also, marine flora’s photosynthesis process has made the ocean the world’s greatest and most vital carbon sink. As microplastics affect the ability of these organisms to grow, reproduce and capture carbon, their presence could accelerate the loss of ocean oxygen.

Regarding microplastics in the air, researchers note that they can impact cloud formation, potentially affecting temperature and rainfall. Moreover, the stronger UV radiation in the upper atmosphere could accelerate the degradation of plastic particles, releasing greenhouse gases and accelerating global warming.

Asia as a Global Plastic Pollution Hotspot

Plastic pollution isn’t an isolated problem since one country’s waste becomes another country’s waste. For example, scientists studying Henderson Island, an uninhabited land in the South Pacific Ocean, found plastic waste from the US, Europe, Japan, China, Russia and South America, that ended up there due to the South Pacific Gyre, a circular ocean current.

While over 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris and 170 trillion particles are afloat in the ocean, nowhere is the problem more severe than in Asia. According to a study, nine out of the top 10 biggest ocean plastic waste polluters are in Asia. The Philippines tops the charts with over 35% of the global plastic waste emitted to the ocean, while India and China have been found to be the leaders in mismanaging plastic waste.

The World Bank estimates that just 5% of total plastic waste generated in South Asia is recycled.

According to a study by scientists from the University of Leeds, six of the top 10 global plastic pollution hotspots are in Asia.

Aside from domestic factors such as the increasing population and growing industrial and consumer demand, a big reason for this dominance is that Asia has long been an importer of plastic waste, including plastics labelled for recycling. However, authorities across various Asian countries, starting with China in 2018 and followed by Southeast Asian nations such as Thailand and Indonesia, imposed import bans. While moves like these could significantly reduce the plastic waste ending up in those particular Asian countries, there are concerns the imports would be rerouted to jurisdictions with weaker controls like Vietnam and Malaysia.

But imports aren’t the most significant problem. The top priority of Asian countries should be addressing the growing domestic demand and production. According to projections by the OECD, emerging economies in Asia could see some of the fastest-growing rates in plastic use.

While plastic consumption is on course to increase everywhere, the biggest growth is expected to be in Asia. Scientists predict that China will see the largest consumption by 2050 (235 million tonnes per year in 2050), while the fastest growth rate of plastic use will be in India.

The Global Plastic Treaty and Other Crucial Measures to Address Plastic Production and Pollution

Back in 2022, 175 countries agreed to form a global legally binding treaty to tackle plastic pollution and waste management, as well as plastic production and design. After several rounds of discussions, negotiations were expected to conclude in December 2024 at a special meeting in Busan, South Korea. While over 100 nations supported a draft to cut the 400 million tonnes of plastic produced annually and phase out certain chemicals and single-use plastics, in the end, the usual fossil fuel culprits, including Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia, obstructed the deal, and parties failed to reach an agreement.

Another round of discussions is scheduled for August 2025 in Geneva, Switzerland. However, it remains unclear if the coalition of the high-ambition countries will manage to get the deal signed or if negotiations will again succumb under the petrostates’ demands.

In the meantime, the world will have to rely on patchwork fixes and voluntary efforts. For example, the EU, the biggest plastic waste exporter, announced it would ban exports to poorer nations outside the OECD from mid-2026 to protect the environment and health in those regions. The union will also introduce stricter rules for exports to OECD countries. Import bans similar to those in some Asian nations can also help tame pollution.

On a national scale, taxation, extended producer responsibility, “polluter pays” schemes and programs for incentivising recycling can prove crucial. In Romania, for example, a simple deposit return system where consumers make deposits when buying beverages in plastic packaging and get their money back when returning the empty container to a designated collection point, has proved highly effective. In just a year, it collected over 3 billion containers, with 84% of containers sold in the market returned through the scheme. Authorities estimate that 70% of Romanians return PET bottles through the system.

It is also crucial for countries to provide communities access to proper waste collection services, as at least 1.2 billion still live without them. As a result, they dump waste on land or rivers or burn it in open fires. This is a much-glaring problem for South and Southeast Asian countries. In India, for example, around 255 million people remain outside the government’s waste collection and disposal programs.

On the business and individual sides, innovations like biodegradable plastics, eco-friendly alternatives like bamboo, paper, corn starch, seaweed or carbon polymers and improved recycling technologies should become mainstream, with companies and consumers making more conscious choices. Governments can accelerate the shift toward more circular and sustainable product and packaging design through laws, regulations and incentives that justify them in a competitive market.

While the Busan meeting proved that a handful of nations can hold the world hostage over one of the biggest ecological problems humanity has ever faced, the conscious side of the market has the tools to reduce virgin plastic demand and consumption. Ultimately, it isn’t a question of finding solutions but a matter of making political and behavioural changes that the whole world can benefit from.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.