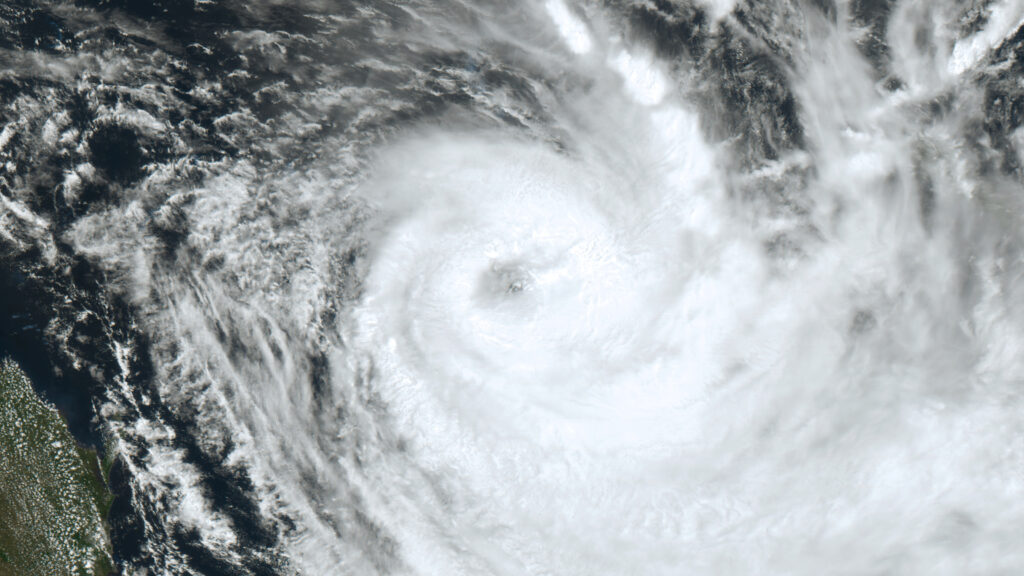

Water supply disruption is widespread across Asia. Heavy monsoon rains, melting glaciers and a severe heatwave – a series of events with climate change as the common denominator. The chain reaction paved the way for the historic floods that submerged a third of Pakistan in 2022. The aftermath: over 33 million people affected, and half of them were children.

Floods in Asia

According to the World Meteorological Organisation, since 2000, flood-related disasters have risen by 134% compared with the two previous decades. Most of the flood-related deaths and economic losses were in Asia.

Aside from the loss of life and infrastructure destruction, flood-related events also contribute to one of Asia’s most glaring problems: water stress. According to the UN, six months after the floods in Pakistan, over 10 million people in flood-affected areas continued to be deprived of safe drinking water and had no alternative but to drink and use potentially disease-ridden water.

From a water-rich country in 1962, today, Pakistan is the 15th most water-stressed nation. Climate change risks further exacerbating the problem. By 2035, Pakistan will become water-scarce.

Water scarcity and increasing water supply disruption are widespread issues across Asia. The southern and central regions are among the hardest hit globally. As a result, countries have to navigate various challenges: from disrupted lives, livelihoods and natural ecosystems to reduced economic output, hydropower imbalances, migration, food security risks and geopolitical tension.

The Scale of Asia’s Water Supply Disruption

Access to sufficient, safe, affordable and physically accessible water is a basic human right. Yet, today, this isn’t a given for a large part of Asia.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), the Asia–Pacific region is home to some of the most water-scarce areas globally. The population under high or severe water scarcity grew from 1.1 billion to over 2.6 billion between 1975 and 2010. While Java, Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City, and fast-growing cities like Kathmandu are the main hotspots for absolute water scarcity, water quality is decreasing throughout the entire region. According to the Asian Development Bank, around 500 million people in Asia and the Pacific lack access to a basic water supply today.

In Southeast Asia, around 110 million people lack access to safe drinking water. Disturbingly, 347 million, or 55% of South Asia’s children, are facing severe water shortages due to climate change. This is the highest rate worldwide. In total, a staggering 74% of the population in South Asia is grappling with high water stress levels. Furthermore, UNICEF estimates that between 68% and 84% of the water sources in the region are contaminated.

While most of Asia is facing water scarcity and increased stress, the magnitude and triggers of those problems can vary for different countries.

China and India

China faces a severe water crisis that risks slowing its economic growth and causing social instability. Various reasons are behind this, including the drying up of its biggest rivers, rising water demand and melting glaciers. Furthermore, up to 90% of China’s groundwater resources are unfit for consumption. According to estimates, 50% of its river water is unsuitable for drinking.

Researchers identify India as the other nation facing the highest water scarcity risk globally. According to the World Bank, despite being home to 18% of the world’s population, its water resources are sufficient for only 4%. As a result, it is the most water-stressed country. For example, just last year, monsoon delays left Mumbai facing a major water crisis, leaving just 7% of the drinking water reserves in the seven dams supplying the city.

Although the two countries face the biggest challenge, they also have sufficient resources to address it through investments in innovation. Other Asian economies are in more challenging circumstances.

Vietnam

The country experiences all types of water scarcity, including too little water, water supply intermittency, poor water quality and overutilisation. A big reason for Vietnam’s water scarcity problems is that around 63% of its surface water comes from transboundary rivers. This makes it highly dependent on the impacts of the actions of upstream countries.

In addition, access to safe drinking water is threatened by the increased rate at which clean groundwater is being pumped for industrial, agricultural and urban use and the inability of nature to compensate for it.

However, natural factors and the worsening of the climate crisis are also playing a big part. This year, the saltwater intrusion in the Mekong River, which 65 million people rely on, arrived a month and a half earlier and was more significant than usual. According to experts, this has prompted recurring water cuts, complicating access to clean water for household use and disrupting rice and crop production. This year’s events continue a steady trend of saltwater intrusion across the Mekong Delta due to rising sea levels that experts have been monitoring for a while. According to the Mekong River Commission, the fluctuating water levels stem from climate change.

Bangladesh

According to the FAO, the country experiences two types of water scarcity – highly variable water and poor water quality. Furthermore, analysis has shown natural arsenic contamination in the groundwater in 60 out of the 64 districts in Bangladesh.

Today, while 97% of the population has access to water, just around 40% enjoy proper sanitation. In coastal areas, people must walk miles daily to access safe, drinkable water.

Furthermore, groundwater is depleting rapidly in the greater Dhaka area, posing a risk of permanent water loss. According to studies, by 2030, groundwater levels can drop by up to 5.1 meters. This is around 70% faster than the current rate.

The magnitude of the problems is so significant that Bangladesh is now approaching a situation of chronic water scarcity. Estimates reveal that it could cost the country’s economy up to 6% of its GDP in 2050.

Indonesia and Thailand

Indonesia suffers from three types of water scarcity: too variable water, overutilisation and poor water quality. Studies estimate that only 10% of rainfall infiltrates the groundwater, while 70% of its rivers are heavily polluted by domestic waste. Increased deforestation and agricultural runoff are also exacerbating the water stress.

Thailand experiences all types of water scarcity, including having too little water supply, too variable water, overutilisation and poor water quality. The water quality issue is a particularly notable problem, widespread throughout the country. Among the main reasons are industrial and agricultural pollution, high population density and low wastewater treatment rates.

Climate Change to Worsen Asia’s Water Stress Problem

There are various triggers for Asia’s water stress, including infrastructure buildup and uncoordinated development, a growing population and increasing water demand, increased consumption for industrial purposes, land use changes and pollution.

However, scientists are confident that climate change and its diverse impacts are among the biggest contributors to Asia’s increasing water stress. The reason is that water and climate change are deeply linked, as rising temperatures disrupt the entire water cycle, including precipitation patterns and droughts, affecting ice sheets and sea levels and causing more severe floods and storms.

According to the World Meteorological Organisation, climate change hit Asia the hardest in 2023. The extreme heat and precipitation discrepancies have caused some countries to suffer prolonged droughts. In contrast, others experienced record hourly rainfall, causing flash floods. In the past year alone, 79 water hazard disasters hit Asia. Over 80% were linked to floods and storms, causing over 2,000 deaths and affecting 9 million people. Furthermore, the global warming-induced melting of glaciers, ice sheets and ice caps has caused Asia to experience higher sea level rates than the global mean between 1993 and 2023.

Floods and Saltwater Intrusion

Erratic monsoons, storms, floods and sea level rise can all lead to saltwater intrusion – a process where saltwater advances through surface or groundwater sources and diminishes the availability or quality of drinking water supplies. Researchers warn that severe saltwater intrusion negatively impacts people’s health and can contaminate soil, reduce crop harvest and change species abundance and diversity. Studies reveal that the countries across the Mekong River, the biggest river in Southeast Asia, face multiple drivers and anthropogenic forces that will increase the salinity of affected areas by up to 27% in the next three decades. Rising sea levels are expected to add another 6-19% increase.

According to the IPCC, sea-level rise is projected to extend groundwater salinisation, decreasing freshwater availability in coastal areas. Furthermore, the scientists warn that the relative sea level around Asia has increased faster than the global average. Their high-confidence projections reveal that the regional mean sea level will continue to rise. As a result, Southeast Asia bears some of the highest coastal flood risk globally.

Droughts

South and Southeast Asian countries are also projected to experience medium-to-high or high drought risk in the upcoming years. Furthermore, scientists warn that the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, which provide water for a billion people in South Asia, including some of the poorest and most marginalised population groups, are all at risk of drying up.

Glaciers Are Melting

Another factor that further complicates the situation is the accelerated warming of the Himalayan glaciers. This vital ecosystem for Asia’s major rivers is one of the world’s largest freshwater sources, of which almost 2 billion people rely on for agricultural use and drinking water. While the glaciers have been forming for over 70 million years, scientists warn that over the past centuries, they have been warming at over 10 times faster than average, leading to the loss of tonnes of ice every year. As a result, they risk losing up to 30% of their mass by 2030 and 75% by 2100, potentially causing dangerous flooding and water shortages. Nepal is the country facing the highest risk.

The China Water Risk think tank notes that climate-related impacts, such as glacier melt and extreme weather, significantly affect the basins of the 10 major rivers in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan water system and the 16 Asian countries relying on them. Unless emissions are tamed, the researchers warn that people relying on those rivers have to brace themselves for compounding and increasing water risks.

The Urgency of Asia’s Water Scarcity Problem Calls For Regional Cooperation

Governments have the duty to respect, protect and fulfil every individual’s right to safe drinking water. To honour this responsibility, it is imperative to enhance regional cooperation on a state level and introduce nationwide policies that protect water supplies and motivate businesses and industry to identify, assess, prevent and mitigate water stress.

Among the top priorities is reducing emissions by accelerating the clean energy transition and slashing emissions. According to the IPCC, limiting global warming to 1.5°C instead of 2°C would approximately halve the proportion of the world population suffering from water scarcity.

On a national level, Asian governments should prioritise sustainable water governance, addressing pollution, ensuring more efficient use and building resilience. Policies for water transfers and extraction reforms and investments in water retention, desalination, irrigation and watershed protection can be key on that front.

Singapore is a glaring example of how investments in water conservation, sanitation and reuse can pay off. Today, the country uses recycled water to meet up to 40% of its water demand. It is also pioneering flood protection and wetland conservation, which is crucial since these areas ensure both a natural shield against extreme weather events and serve as carbon sinks. According to the World Risk Report, despite the significant climate risks it faces, Singapore is among the most disaster-prepared nations globally.

The magnitude and complexity of the water scarcity problem call for a collaborative approach and transboundary cooperation. So far, there have been geopolitical tensions and local conflicts across Asia, with countries having disagreements and raising concerns about waterway management and resource use. However, it is imperative for nations sharing common water resources, like Asia’s biggest rivers and the Himalayan glaciers, to join forces and collectively address issues that they all individually face. Engaging in water diplomacy with national initiatives, supported by international aid and transregional collaboration, is a much-needed way forward to ensure more efficient and sustainable water resource management and address the increasing water scarcity risk.

Knowledge sharing is also crucial. Since authorities in floodplain regions already have deep knowledge in addressing floods, they can help counterparts in coastal zones learn, prepare and respond to evolving risks.

On the other hand, failure to progress on these measures poses significant humanitarian, political and economic consequences.

Asia’s Water Scarcity Risk Requires Immediate Attention

For much of Asia, the climate change-exacerbated water crisis is no longer a distant, gloomy projection but an everyday reality where communities are deprived of their basic rights. Its implications are widespread and severe, and without immediate action, acute water stress will continue hurting the health and livelihoods of hundreds of millions and disrupt wildlife and natural ecosystems.

Furthermore, it can also trigger escalating regional and global conflicts, an idea that has been mostly present in sci-fi books. However, as recent events show, the line between fiction and real life is beginning to blur.

Viktor Tachev

Writer, Bulgaria

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.

Viktor is a writer that specialises in green finance and ESG investment practices. He holds a Master's degree in financial markets and has over a decade of experience working with companies in the finance industry, along with international organisations and NGOs. Viktor is a regular contributor to several publications and comments on the likes of sustainability and renewable energy.